“No new pictures until the old ones are used up!” Joachim Schmid begged near the end of the 20th Century (without much success).

There were to be new pictures, a lot of them actually, as photography became the currency of the internet. The futility of Schmid’s plea should not divert attention from the underlying idea, an idea that is as relevant today as it was thirty years ago: we ought to not just make photographs, we’d also be well advised to look at them — specifically to understand what they do and how they do what they do.

This approach to photography is not new. While working with other people’s (“archival” or “found” or “vernacular” or whatever else) photographs became an established part of both the larger art and the much smaller photography world (with some overlap between them), it’s worthwhile to remember how the first truly relevant attempts in that direction were worked on during Germany’s Weimar Republic. Unlike today, the people engaged in looking at photographs to understand their meaning — and this meant the meaning as derived from their use — were theorists and artists. Writers Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer were just as interested in understanding photography as artists such as László Moholy-Nagy or Aenne Biermann (both Moholy-Nagy and Biermann published books entitled 60 Fotos, the former one’s still well known, the latter one’s now being more or less forgotten).

In a day and age where artists frequently use archival materials to add to their own projects, the critical aspect of working with other people’s pictures has mostly fallen by the wayside (especially since Christian Patterson‘s Redheaded Peckerwood became a much emulated model for creating narratives in book form). Archival photographs are mostly included because of their use value and less so to focus attention on their very essence. In fact, archival materials tend to often be used when they’re extraordinary, when, in other words, beyond their patina there is a sense of strangeness or attraction to them. After all, who would want to work with mundane, if not outright boring source materials?

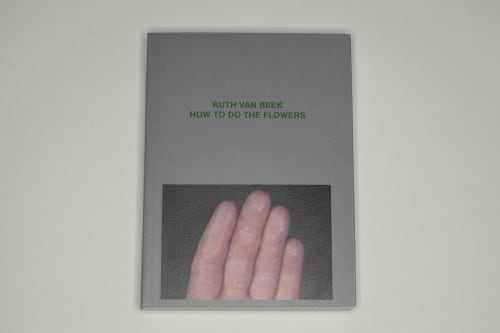

Well, Ruth van Beek would. There is not a single truly memorable photograph in How To Do The Flowers, yet the accumulated effect of paging through over 500 pages of banal pictures that are arranged in a large variety of montages is extraordinary.

The book has much in common with Batia Suter‘s Radical Grammar or Parallel Encyclopedia. In both cases, the authors sourced their material from a wide variety of original publications. However, unlike Suter, Van Beek eschews attempts to showcase her visual intellect. Make no mistake, that visual intellect is very much present. But it’s employed in the service of something that ultimately is completely nonsensical and that is brilliant because of it. It’s sheer Dada. In a world of photography that all-too-often is concerned with an artist’s (supposed) cleverness, Van Beek’s dry wit is most welcome.

As one might expect, many of the photographs used in How To Do The Flowers appear to have been taken from books in which photographs were supplied to visually support instructions. Photography is great for that: you want to learn how to do something (bake a cake, make a doll, take care of a cactus, …)? Well, here are the steps — inevitably, things will be reduced to a set of finite steps, and here is what the steps look like, meaning here is a person going through these steps, and here are pictures of that person — often just the hands — engaged in baking a cake, making a doll, taking care of a cactus, …

Of course, YouTube videos have largely taken over the role of such instructional books. Say whatever you want about the utility of such videos, the kind of photography not being produced any longer that Van Beek has been mining here is a tremendous loss: the most utilitarian photography is often the most amazing once it’s taken out of its original context (c.f. Sultan/Mandel’s Evidence).

How To Do The Flowers is filled with photographs of hands doing something. Since originally preceding and following images are absent and since furthermore there usually are montages that juxtapose images, the effect of looking through the book is completely arresting. This is in part because the viewer’s expectation concerning these source photographs has not become completely untethered from them. They look like they should make sense, yet out of their original context, they’re like Wile E. Coyote hovering above the inevitable abyss.

Van Beek deftly works these expectations against one another or with each other, to produce a Dadaesque cabinet of instructions: if a viewer is somehow going to learn something for the book, for sure that knowledge will be utterly useless.

So the viewer will end up having to submit to the uselessness of it all, which provides a tremendous sense of relief, given that the world of the photobook tends is filled with books that each “explore” one important or grave or very relevant topic after another. I will admit that at times, the sheer joylessness of this world frustrates me deeply. It’s certainly not that I feel the need to be entertained all the time — on the contrary. But the onslaught of often half-baked cleverness in the service of some topic that in the larger scheme of things often might not be so important is relentless.

Given Listmas, the season of endless “best of” lists is upon us, I think I’d like to conclude with one very basic personal observation. Despite the reservations I just mentioned, this past year has renewed my faith in the photobook. There have been quite a few very impressive ones — if you browse through my archives you will find many of them reviewed. I don’t know whether How To Do The Flowers is going to be the last book that I will be able to add to all those that had me enjoy this year so much. But for sure it is one of the books that I had been very much looking forward to, and I’m so delighted that it didn’t disappoint.

Highly recommended.