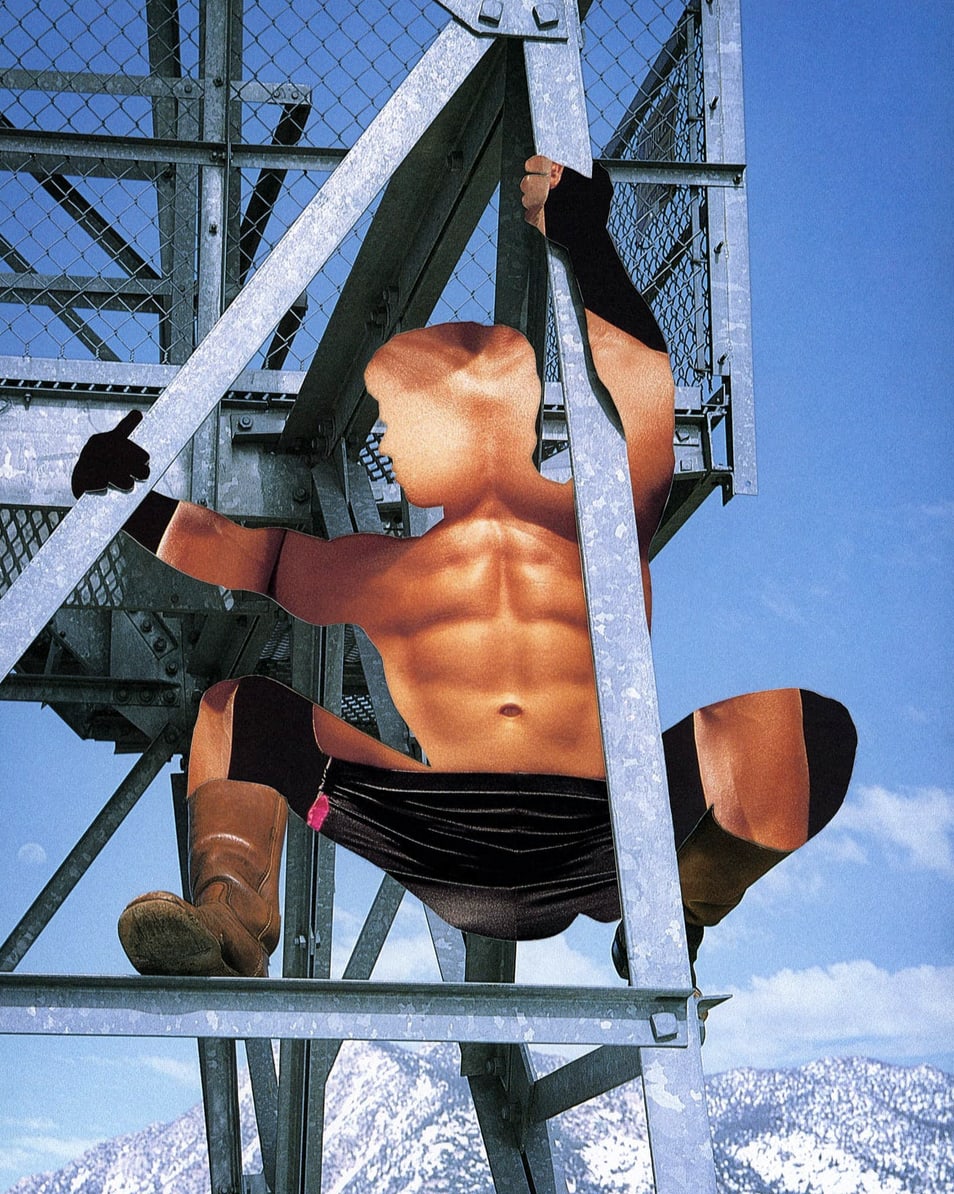

Michael Young disassembles gay calendars as a metaphor for his closeted years.

Michael Young’s “Hidden Glances” is a series of handmade cutouts from erotic gay calendars spanning the time he hit puberty until the day he came out, collaged and reimagined. Young overlays images to compress time and space – years he sees as a void of hiding in plain sight.

The resulting images (even those rendered in black and white) are bright and colorful, contrastingly balancing joy, fear, and a memorial to time lost. They swell and sweat eroticism and desire, hanging with regret for the time he could not publicly acknowledge his true self.

“When I wanted to look at guys,” Young writes, “I could only risk taking quick glimpses because I was afraid that my gaze would linger too long and expose my homosexuality.”

We're proud to include Young among 10 artists Humble is spotlighting as jurors for Photolucida's 2021 Critical Mass. Roula Seikaly and I selected work we find truly remarkable in vision and concept, and Young is a shining star among many talented artists. For a limited time, Klompching Gallery is offering a super affordable edition of Young's work HERE. Get one before Gagosian snaps him up!

I spoke with Young to learn more about his work, his evolution as an artist, and his use of “reverse collage” as a powerful metaphor.

Jon Feinstein in conversation with Michael Young

Stripes, a Tank and a Towel, June © Michael Young

Jon Feinstein: There is so much to discuss here, but let’s get at it from the beginning. How did Hidden Glances start?

Michael Young: This series started by chance. I had begun work on another project loosely based on my grandfather’s time spent in the Navy during the Korean War. As I was collecting different types of material through eBay, one of sellers, from whom I was buying 1950s beefcake magazines, began to include 1990s gay calendars as little extra gifts.

I grew intrigued by these calendars and so I began to buy them whenever I could. At first I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with them, but my interest was piqued. I felt like a kid finding a hidden stash of porn for the first time. As I flipped through these calendars from the ‘90s I began to think about my own past and all those years I spent in the closet before coming out in college.

When I put aside my other projects and finally decided to work with the calendars, I knew that I wanted the final images to have a nostalgic feel and show the way I was physically manipulating the materials. This is why the creation of the works happens on a cutting board rather than in Photoshop.

The Alps, December © Michael Young

Feinstein: Yes - while I think these might still be effective if they had been made digitally, the analog-ness of them feels vital to the concept. Why was this so important to you?

Young: Maintaining this analog approach to the construction of the image pays homage to the beefcake magazines and calendars that were created and designed manually. Given that the calendars were produced before Photoshop became popular, I made a conscious decision to use a hands-on approach when making these images.

By spending time deconstructing, making cuts with an X-Acto knife, and manipulating the original photos, I forced myself to make choices that would be destructive. This practice allows the work to live both in the past and the present.

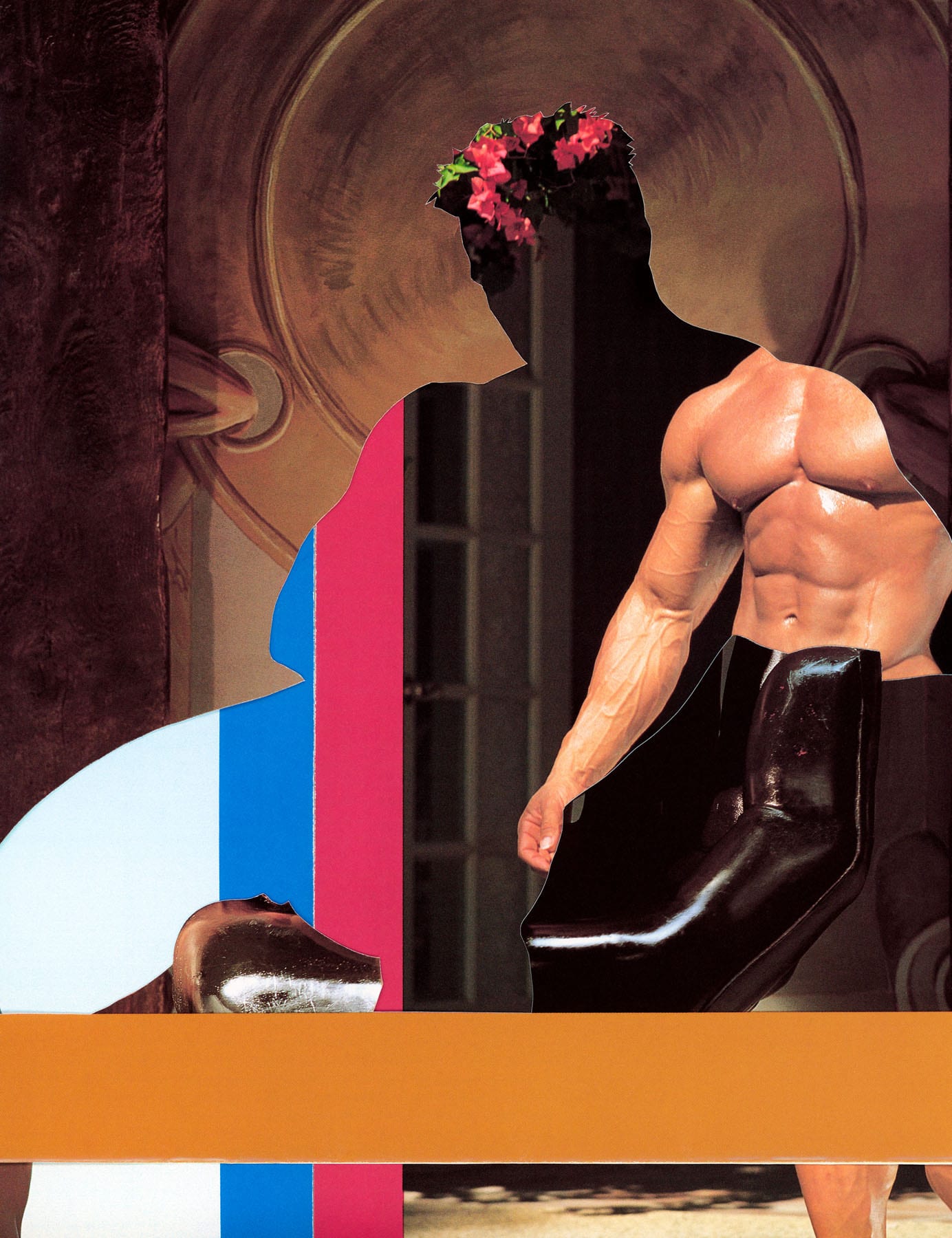

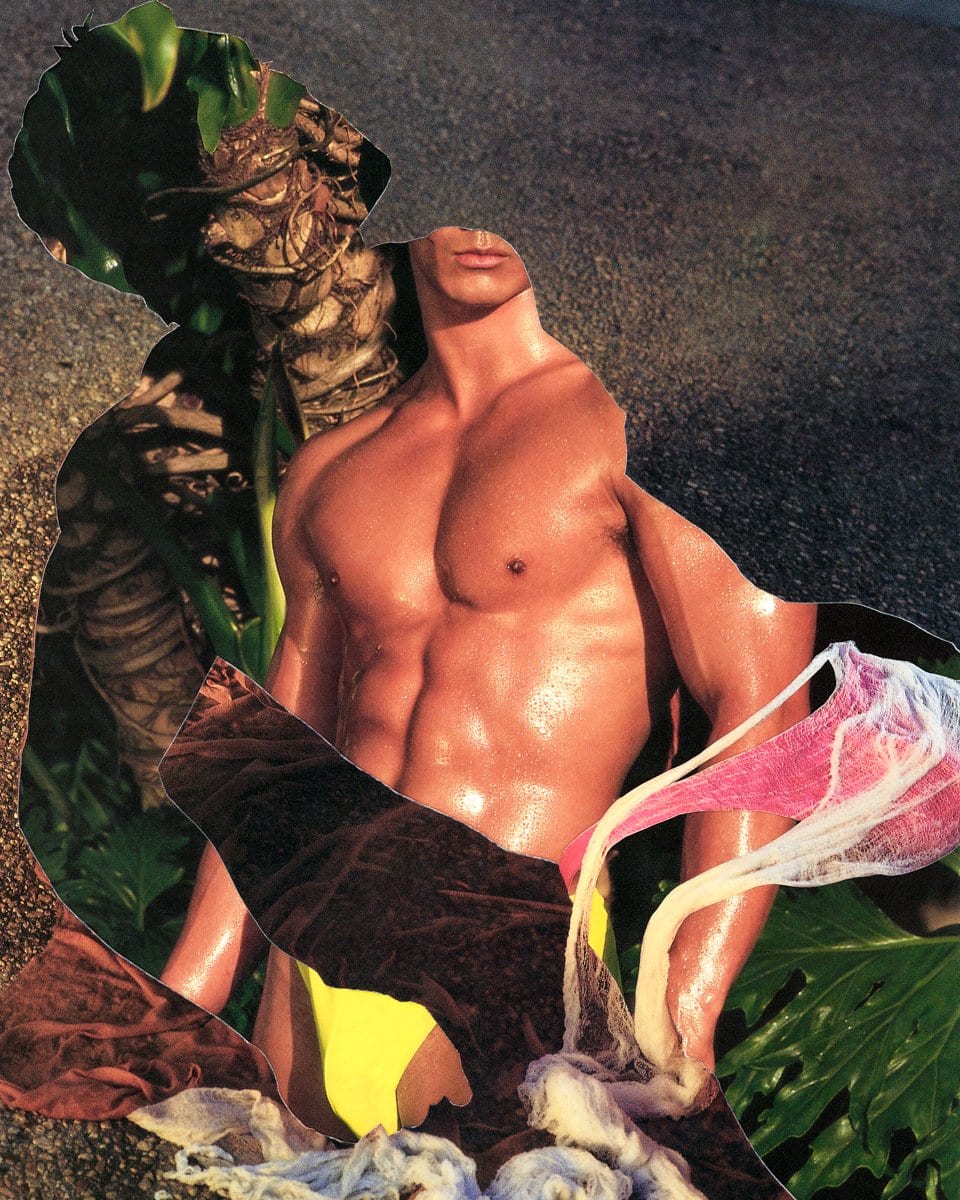

Crown of Bougainvillea, October © Michael Young

Feinstein: You describe this series as coming out of your “lost years" – the period of time before you came out in 2000. If you feel comfortable talking about it: can you take us on that journey - personally, and within your process?

Young: When I compare myself to my classmates who identified as heterosexual, it was okay for them to talk about their crushes, go on dates, and hold hands while walking down the hallways in school. For me, those years were built around constantly making up excuses as to why I didn’t have any girlfriends. To shield myself from further questioning, my go-to answer was always that I was involved in a lot of extracurricular activities and wanted to keep my grades up so I could attend a good college.

Although everyone who comes out has their own story, and they may be vastly different than my own, I do think that guys my age do share a similar sentiment about coming out, and it’s that feeling that I try to convey in the visual components of my work. Those feelings of simultaneously wanting to be seen while also holding back a part of who they are from the rest of the world.

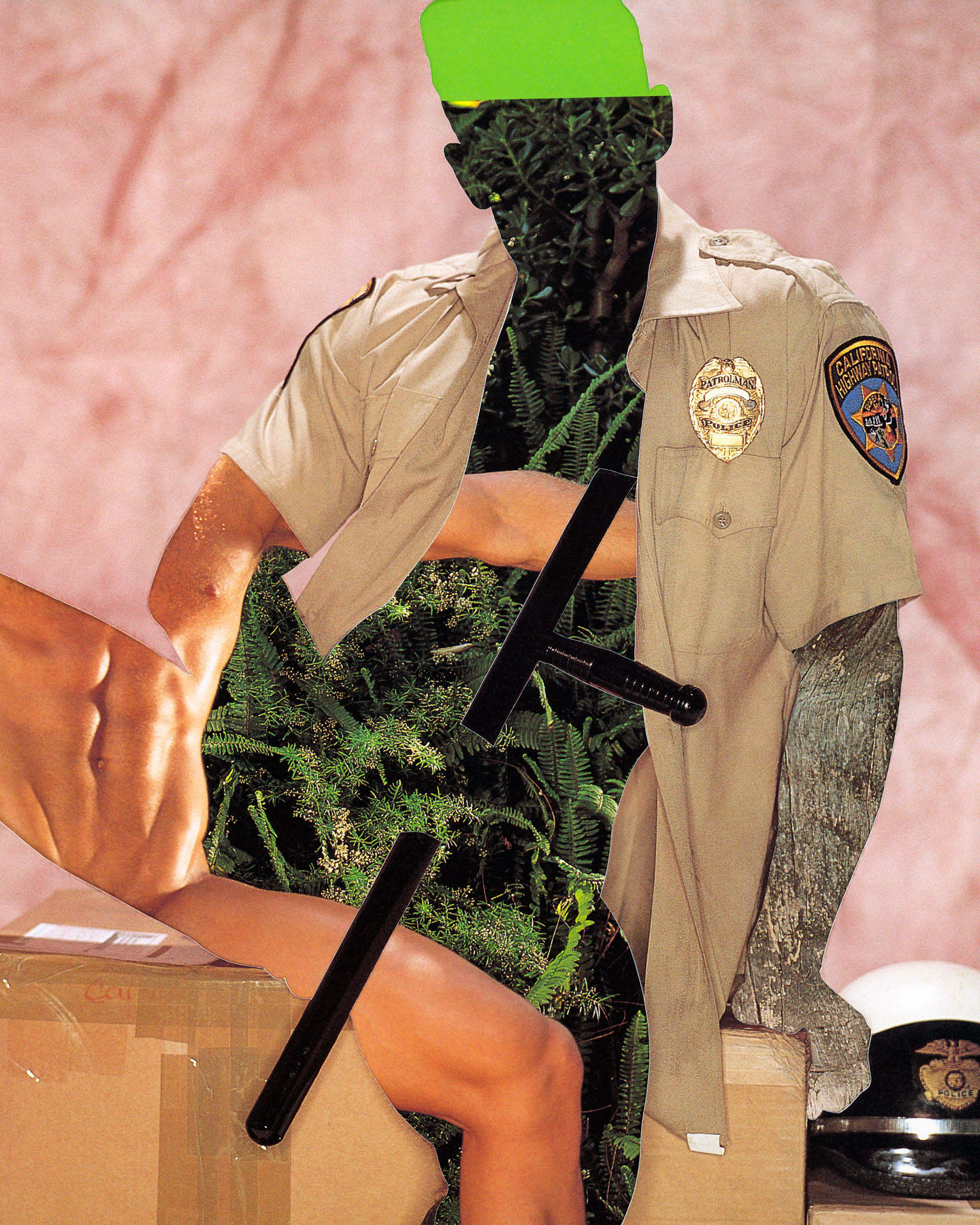

California Highway Patrol, May © Michael Young

Feinstein: Has making this work helped you make sense of that?

Young: It has. Making this work feels exciting, a bit naughty, and in some ways quite the opposite of my introverted self. However, even when I went off to college at Yale, coming out still was not something that I was comfortable with and it was a struggle for me. In certain ways I would say that I’m still a work in progress even to this day when it comes to fully embracing who I am, and so I suppose this series is therapeutic for me.

Feinstein: While the found images are from gay calendars, I'm also interested in your selection of the backgrounds and how that plays into the ideas, feels and personal history behind this work.

Young: To keep the work related to my personal experience this series only uses gay calendars that were published between 1979 and 2000. I then work with one calendar at a time and confine myself to create images from the 12 photos published within that one calendar. Sometimes I get a bunch of great images while other years lead me to a whole lot of nothingness.

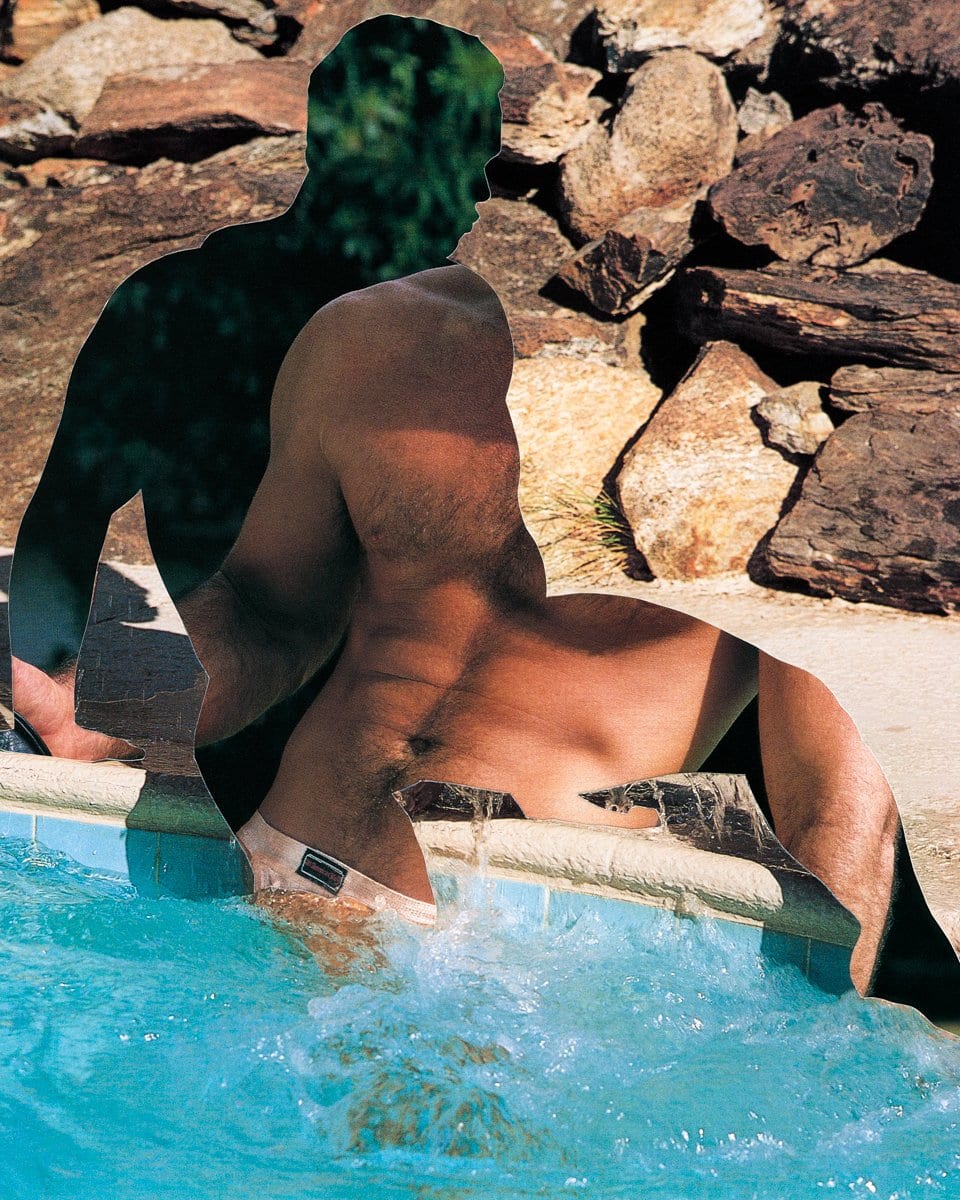

Poolside, May. © Michael Young

Feinstein: What draws you to a specific image to work with?

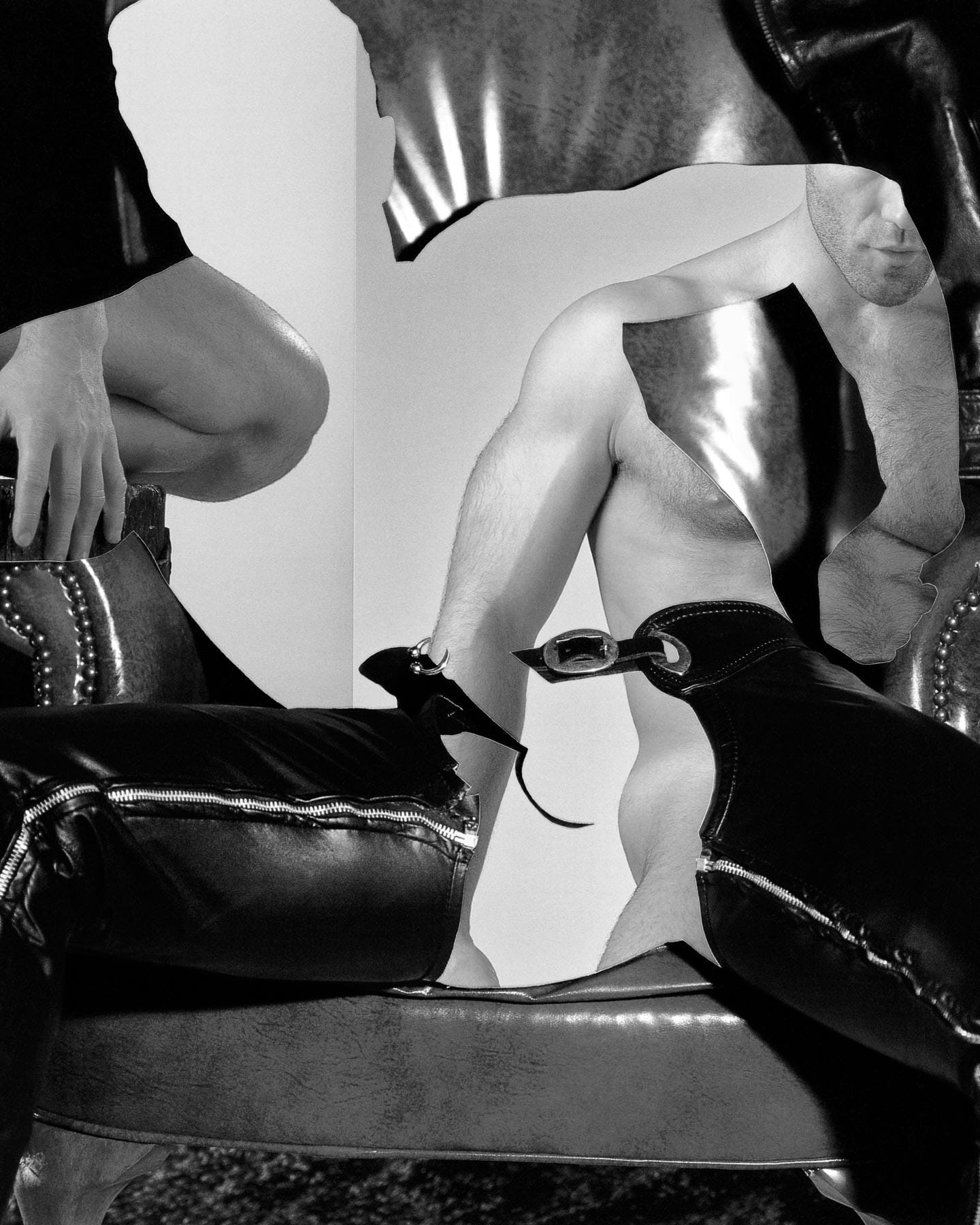

Young: When making the work, I am drawn to pairing images that have strong silhouettes in profile along with scenes that aren’t shot against a solid background. The tricky thing with these types of calendars is that many times the figure is placed directly in the middle of the frame so creating dynamic compositions can be tricky. Since I have only been combining two images into one, the way I will sometimes “cheat” my own rules is by cutting the background image and then rearranging it so it appears that there may be more than one figure in the background. You can see this in the work Leather on Leather.

I also like creating works where the images do not resolve themselves at first glance. For me, the works that are most successful are the ones where the viewer is forced to do a bit of work moving between the foreground and background. I am drawn to creating images where the silhouette and the figure in the background begin to merge and the space is blurred and compressed.

As for the backgrounds, when I am working on creating a new image, I am typically drawn to images that have a background that invites the viewer into the compressed space.

For me, there needs to be a visual hook that keeps me coming back to the image. And as for the image and model that resides in the background, I am always looking for it to create a dialogue with the top layer. Sometimes it’s based on disparate colors, other times it’s how the lines of the cuts from the top layer connect to the bottom to lead the viewer’s eye back and forth between the two layers. Other times it’s to create a sort of visual dissonance or abstraction that enhances the ambiguity of the two figures in the work.

Leather on Leather, February © Michael Young

Feinstein: Ideas around “revealing" vs "concealing" are a big part of this work.

Young: Since I spent many years trying to hide my true identity from others, I thought that I had become a true master at concealing my true identity, though for others it most likely came off as a sham. For this reason the concept of revealing versus concealing is an essential component of the work.

This concept also speaks to the internal push and pull that existed within my own desires prior to coming out, especially when I wanted to flirt while also remaining “straight” to others. That being said, my works play with the idea of looking, hiding, and being seen. They also shift the original material from being blatant depictions of pornography to works that retain their seductive quality while visualizing those fleeting glimpses that someone not out of the closet would try to make without being outed.

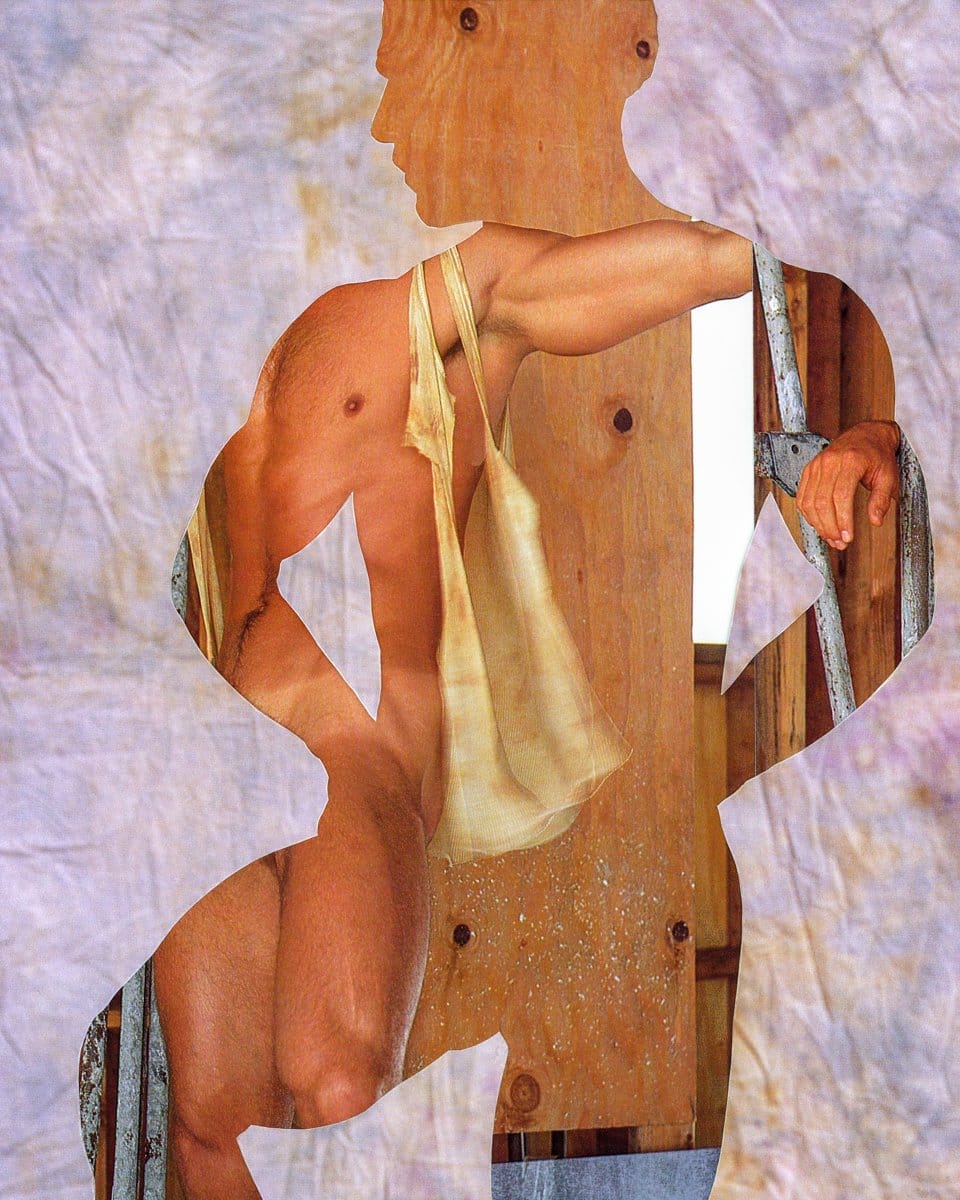

Behind the Backdrop, April © Michael Young

Feinstein: How does that manifest itself visually?

Young: My hope is that the viewer becomes part of the game of looking and being looked at. Furthermore, I am drawn to the creation of images where the overlays create a compressed visual space that both invites the viewers in but also keeps them away.

Feinstein: That makes so much sense! The majority of the images are faceless silhouettes, but occasionally, an eye, or a glance pops in. This feels deliberate in its pacing and cadence.

Young: In the gay world, it is all about the eye contact and the gaze that lingers just a fraction of a second too long. That’s when you know you’re being checked out by someone else whether it be at a bar, on the subway, or walking down the street. My partner says that I tend to be quite oblivious when it happens to me, but it is something I’m drawn to when creating my work. I want the viewers to feel like they too are being seen by the work--dare I say cruised by the models-- and that the men that they are viewing are not the only ones being objectified.

Peering Through Paper, June © Michael Young

Feinstein: One constant for me in all of this work – even in the black and white images – is a kind of golden light. Is light in the original source material guiding how you select the images you collage and cut up

Young: It’s interesting you mention golden light because it’s something that I never noticed in my work until you posed this question. I suppose that my training as a photographer has always drawn me to light. I don’t think anyone can deny that there is something special about that short span of time each day when everything glows and feels magical and one’s attention is drawn to the light and the shadows it casts. Besides interesting shapes and silhouettes, the lighting of the figures helps me choose the photos I work with.

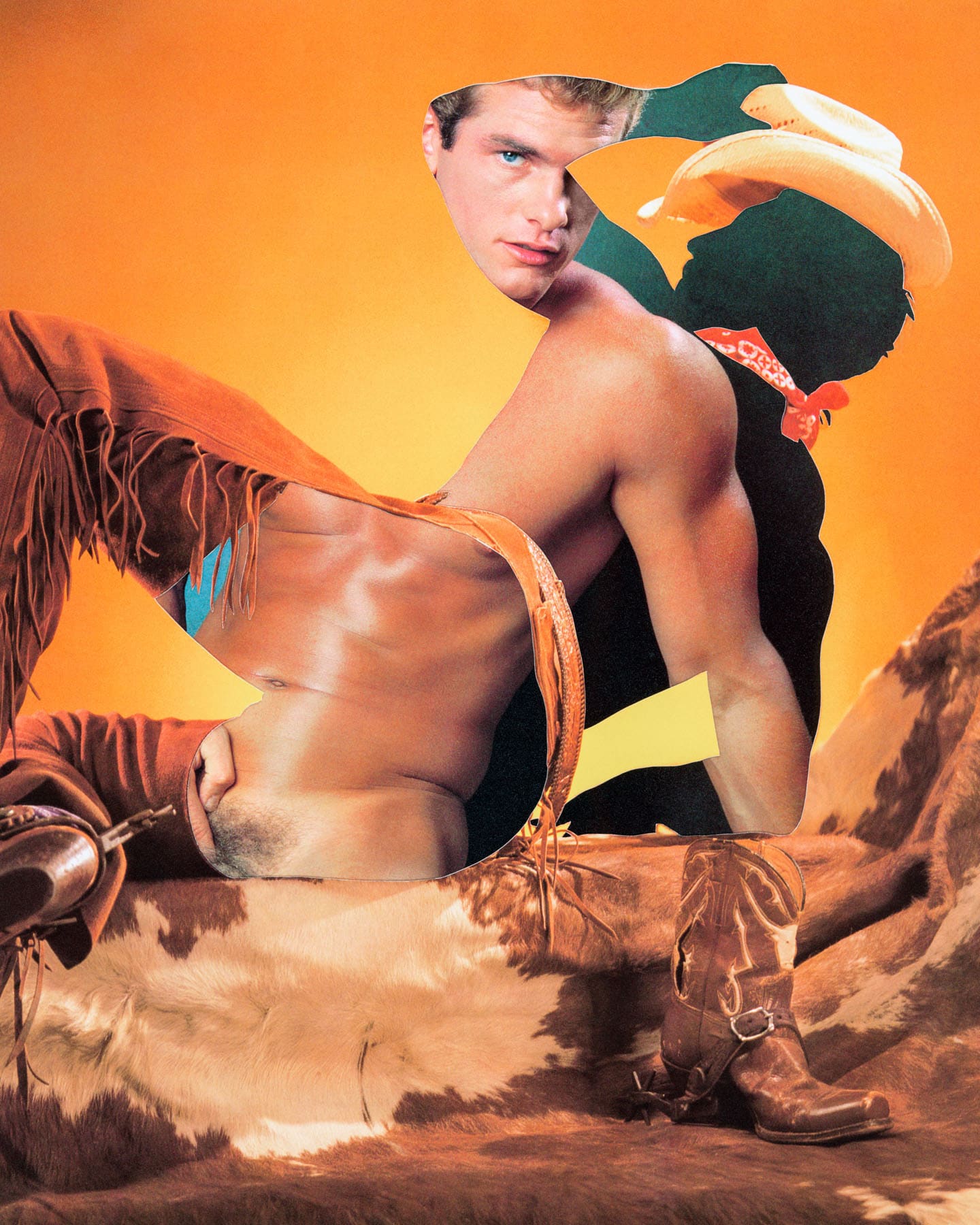

Reclining Cowboy, March © Michael Young

Feinstein: Shifting gears slightly, from Fresh to Critical Mass and so much more, you've been receiving many accolades for this over the past 6+ months - congrats! Has this recognition influenced how you think about/make, etc the work and the story behind it?

Young: To be completely honest, it has come as a bit of a surprise to me. I did not expect what I viewed as a side project to now become the work that is first associated with me as an artist. Prior to Hidden Glances I would have to say that my practice was documentary based. My series about my partner Erik’s family out in western Kentucky has been an ongoing project that I will always revisit and continue to develop. But since we were stuck here in the Northeast for so long, I needed to make work and so I started to pursue other options and themes.

Three Guys, August. © Michael Young

Feinstein: It feels kind of freeing too!

Young: Absolutely! I wanted to give myself the freedom to play a bit more with the medium and in doing so this series came about. Both the Korean War project and this series are bodies of work that allow me to work alone and in the comfort of my office/studio space in my apartment. Having the freedom to explore has been a great way for me to free up my process and evaluate what it means to be a photographer and an artist. As someone who tends to be quite controlling, forcing myself to experiment with different materials and approaches has given me a newfound way of looking at my process and creating work.

Black Sand Beach, July © Michael Young

Feinstein: Do you have a sense of what shifted your process and what ways of seeing remain the same?

Young: This work is a huge departure for me not only in terms of process but also theme. In a way I am returning to work that is more personal for me, and I hope that it resonates with others. While my earlier work was more representational and considered more straightforward in terms of its photographic approach, I believe that there are still many components that I have transferred over. The way I see and compose seems to remain the same, but I think I have always strived to allow for images to either present themselves to me or come about in an organic way.

Founded in 2005, Humble Arts Foundation is dedicated to supporting and promoting new art photography.