-

In his solo exhibition, The Keys to the Factory, French artist Jean-Vincent Simonet presents several bodies of work which derive from his own personal history; each one finds roots and inspiration in a commercial printing factory that remains in his family’s hands. Working on site as the machines sleep was a chance for the artist to recalibrate his relationship to the business – a relationship riddled with particular complexities. Here, Simonet recalls the origins of his interest in materiality and experimentation, which remain constant features of his hand-finished, unique works.Interview by George King.

-

-

-

-

"Whether it was video games or skateboards – normal things teenagers are connected with – the most interesting thing for me was always the related visuals and graphics." - Jean-Vincent Simonet

GHK: You’ve maintained an artistic practice for some years now, but maybe we could start by talking about your younger years. Was it clear you’d end up doing something creative?

JVS: I had a pretty typical childhood. A normal family, a small village, nothing special. But I always remember being quite into graphics and images at different times of my life. Whether it was video games or skateboards – normal things teenagers are connected with – the most interesting thing for me was always the related visuals and graphics. It might have been typography, skateboard stickers, graffiti. I had a camcorder to document the skateboarding stuff, so there was a link to producing, too. This was also when computers were coming into houses, in the late nineties and early noughties; my parents weren’t into technology at all, but I asked for a computer and started cracking photoshop, playing around with those tools. I wasn’t really painting or drawing; I liked the technical stuff – creativity mixed with tools! I was also quite into science, but more for its aesthetics – stuff looks cool through a microscope, or if you mix some vinegar with bicarb! I guess it was for the vibes and visuals rather than the science itself!

GHK: And how did your arts education come about?

JVS: I was lucky! I received some excellent advice from various people to check out ECAL, an art school in Lausanne, Switzerland. I don’t know how it happened, because I had no artistic background or art historical framework, but I got in. From there, everything changed. When you arrive, you get those art historical classes, but ECAL is also quite particular in its own style, its own way of teaching. I was like a sponge! So I went a little further towards a more classical path into photography – learning photography techniques, graphic design, editing, videography etc.

-

-

GHK: What kind of stuff were you playing with in your art school days?

JVS: I was there at a particular moment when digital was really overtaking analogue. The Canon 5D had come out, which had started to surpass the quality of analogue. We were at a kind of bridge: we were still very much being taught about analogue, medium format, scanning, printing. For me, these things were fascinating discoveries; they had a bit of that magic I described in those childhood science experiments! So, throughout my school years, I was mainly shooting analogue. The school had fabulous facilities, great scanners, everything.

GHK: And what ideas where you exploring back then?JVS: In the first year you do smaller assignments, you don’t really go too deep in your research. Instead, you’re building a set of tools. By the third year, I had a bit more space to think – the school gives you that space – and I was sure I didn’t want to do one thing, to be consistent with only one technique. I decided to use this surrealist book of six songs – The Songs of Maldoror writtenby Le Comte de Lautréamont in the 19th century – as a starting point. It’s this really violent, teenage text he wrote when he was 23, and he died just after; it’s a crazy story. I wanted to recreate the six songs, each related to subjects in the book, like romanticism or surrealism, through photography.

Because the subject matter was difficult to capture, it pushed me to do some experimental stuff with photoshop, digital paintings, fucked-up photograms! It was a mixture of all the tools I’d gathered during my study into something really dense. Black and white 4x5s, iPhone pictures, glitching – it was super diverse. It came together in six booklets, each with its own aesthetics, and it felt really fulfilling to explode a bit what could be seen as photography. Nowadays things are so different, but at that time it was pretty unusual to destroy your images with software! And the project went well; it was later exhibited at Foam and featured in their Talent issue. I stayed at ECAL for a couple of years to work as an assistant part time, began experimenting a bit more as a photographer, and then I moved to Paris.

GHK: Do you see a big shift between your projects then and now?

JVS: I think everything is linked, it’s not like something drastic happened and my mind switched. The Maldoror project is really a teenage project – everything’s very strong, intuitive, it’s quite punk.

GHK: There’s some teenage angst in there!

JVS: Yeah! When you graduate you’re only 23, and you can feel it! But it’s been a few years and I’m a bit more calm now! The aesthetics might also be changing; I think I’m more restrained, not everything has to be pushed to the maximum anymore. Maybe I have more trust in myself to make subtle choices now? It’s stupid, but getting recognition can also help you trust your ideas. You just grow up – even though I still consider myself young! So there’s definitely development, but this idea of using both images and photographic tools as material – not as the final thing – is a constant. It’s about materiality, blurring the idea of what a photograph is, setting aside the relationship of photography to reality, to depiction and truth.

-

-

GHK: Your most recent projects – which come together in The Keys to the Factory at The Ravestijn Gallery – all orbit a printing factory that’s been in your family for several generations. Before we discuss the work, what’s the story of this place?

JVS: Well, the factory was first run by my great grandfather. He was an only child, he married an Italian woman, they settled somewhere between Lyon and Grenoble. He was first working for a woman who owned the factory, but she eventually stopped and he took over. It was then passed down to my grandfather, whose three sons – my father and my uncles – now run it. It’s a whole family thing!

My father is an offset driver – he’s really the one printing. One of his brothers is manufacturing (folding, cutting etc.), and the youngest brother does the administration, taking care of clients for instance. Luckily, the business is still doing well, despite the decline of printing. They don’t print fancy books there – it’s stuff like catalogues, stickers, labels for packaging. Everyday printed material linked to industry or big distribution. It’s also a bit more relaxed now, but when I was a child my father was always there from 6 in the morning until 8 in the evening! It was very intense; life was all about work. They come from a very humble background, of workers from the field, so they all share these very strict working values. The factory is life for my father, and of course for my mother, even though she doesn’t go there. The place sets the rhythm for the whole day. That’s what I remember from childhood.

-

-

GHK: And how else did the factory shape you in your youth?

JVS: Of course, when I needed some pocket money, I had to go and work at the factory! It’s funny, I now realise that when you do this kind of job – packaging materials, boring tasks like that – your mind is escaping. You start thinking about other things. Subconsciously, maybe I was already fantasising about certain corners of the space, particular tools, I don’t know! But there was this collision between the things I was absorbing there and the things I was doing in my spare time. There was an encounter between what reality is and how to escape it, to represent it. So, although it took a bit of time to come back to the site, it makes sense for me to make some work about it. Likewise, if the factory’s sold when my father and his brothers decide to retire, maybe it will be a nice way of remembering it.

GHK: Where does your frustration come from?

JVS: It’s maybe a matter of education. The factory means work – it was the tool my parents used to teach me how to behave. This idea that you have to work hard at school or else you’ll end up at the factory! Of course, when working as a photographer you also have to broaden your mind. At ECAL, my parents didn’t have a clue what I was doing; luckily they were nice enough to let me try, but they reminded me where I’d end up if it didn’t work out! So that’s part of the pressure I felt, and that’s also why one of the projects is called Heirlooms – in part, it’s about inheriting that mentality of physical work above all else. I’m glad I was taught those values, but they can also be quite strict and narrow-minded. If you work in a place like this, you’re too tired when you come home to be able to read or watch movies, to stimulate your mind. So, in everything I do, I try to take note of my family’s tips, but also to find a balance with another way of life.

-

Jean-Vincent Simonet

Heirloom no. 08, 2022inkjet on plastic, fingertip intervention, handmade lead frame with museum glass

49 x 69 cm

Unique piece -

GHK: When you grow up around something, you can take it for granted; you might not think of it as a resource. So when did you realise the creative influence of the factory?

JVS: It went step by step. At the beginning, I was just using the factory as a place to print a dummy for a project, to try out a sequence of images or whatever. I was basically just printing things for free! Slowly, I started to think about trying to make something, I had an idea to do something around the mistakes in inkjet printing, so I was trying that out on some editorial fashion assignments, but it really wasn’t working! I was doing tests, trying to scan things, going there once every couple of months.

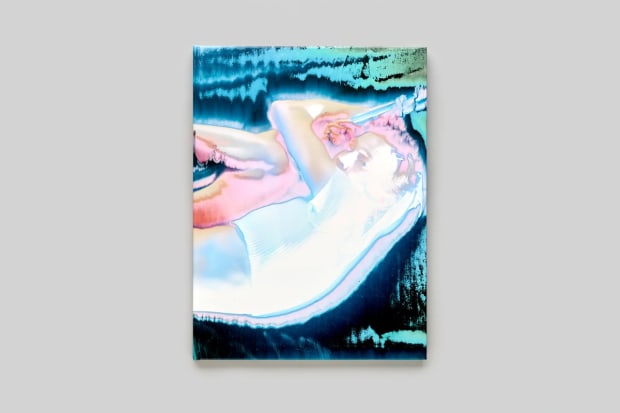

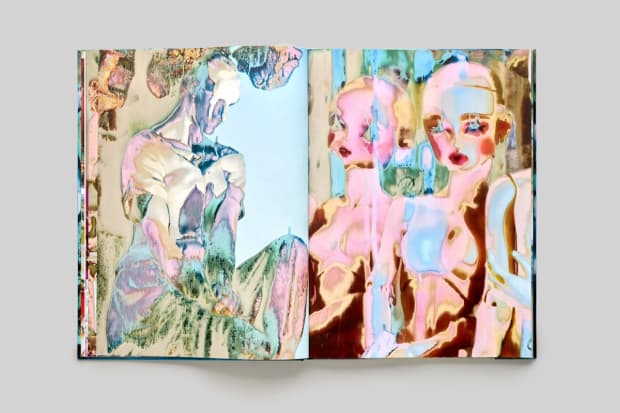

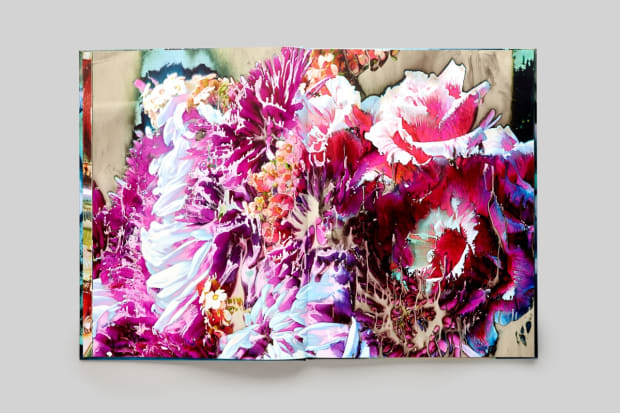

At some point I started to make In Bloom, this project about Japan. Within In Bloom, one part features some of these inkjet prints on plastic – but it was very uncontrolled. That was the trigger. From there I explored and refined this technique, which led to some gallery shows of these works. I was going to the factory to produce prints for these shows, but it wasn’t yet as intense as Waterworks – a publication I made later – for which I really worked on site from early in the morning until late at night, a bit like my father! It was during the summer break, so I was alone. If I’m there with the staff, I try to stay as invisible as possible because I don’t want to interfere with their work. But in summer, everything is mine – I can put stuff everywhere, go crazy on weird experimental stuff, print stuff I wouldn’t normally print when there’s too many clients around! That was a big switch, and I became much more meditative in the space.

Below the last availalbe works from In Bloom.

-

"Yeah! When you go there during the day, it’s so loud. There’s all these industrial noises, lots of people are packing the products, there’s neon lights, it’s alive." - Jean-Vincent Simonet

GHK: You’ve described it as a bit of a Night at the Museum experience?JVS: Yeah! When you go there during the day, it’s so loud. There’s all these industrial noises, lots of people are packing the products, there’s neon lights, it’s alive. When I was first going there on weekends or at night – normally to produce some stuff quickly – the mood was totally different. Maybe even a bit creepy! When I’m painting with my fingertips on the surface of the image, it’s an intimate moment I probably wouldn’t have if others were around, or if I was being observed. It’s not usual to see an industrial space in this state, because everything’s designed to be on as much as possible! I like this poetic idea of all these machines sleeping somehow.

GHK: I guess you’re a bit like a ghost – haunting the space after hours!JVS: Yeah, exactly! -

-

"The fact that they’re printed about 2 metres high creates the feeling of an abstract painting. It’s the idea of creating contrast between the small prints from Heirlooms and these big prints." - Jean-Vincent Simonet

GHK: So let’s talk now about the works themselves. I believe there’s a few projects on show in the exhibition?

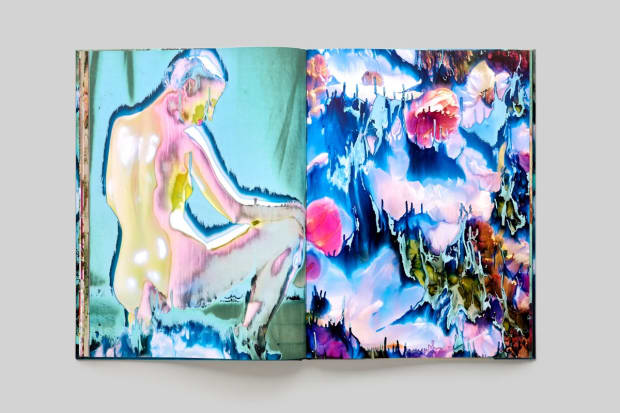

JVS: Yes. So there’s bodies of work from different times. There’s the Heirlooms project, which was the main impulse of the show; prints which include distorted views of the factory itself. It’s the third time I’ve shown the Heirlooms work, but with different prints in each instance. They’re all unique – which makes the project feel quite organic. Then there’s Waterworks, a book I created with the French publisher RVB books in 2021. The images within aren’t at all linked to the factory itself – but the books were produced one summer in the factory. It was in the process of making the book that I started to connect more with the space, visually and physically. From there I started shooting while the prints were drying; the things around me were slowly becoming interesting.

Alongside those two projects, there’s these huge prints – called The Keys to the Factory – which are kind of a new thing: macro shots of the factory’s machines. The fact that they’re printed 2.5 metres high creates the feeling of an abstract painting. It’s the idea of creating contrast between the small prints from Heirlooms and these big prints.

There’s also a kind of sticker installation in the window, to evoke the feeling of entering a church in a way. This installation features an even bigger print of a small detail, very abstract, nice colours, a bit more open to interpretation. In these works, the bigger something is printed, the smaller it tends to be in reality, so there’s this kind of macro perception of the space which is also important in the texture of the print itself. The fact I’m printing on plastic blurs this border between photography and something else – painting, maybe.

-

GHK: What might this sliding scale – this impression of zooming in and out on the factory – evoke?

JVS: I think these macro views of the machines cut the viewer off from the context a bit. In Heirlooms, by contrast, you can see the entrance of the factory; it’s clearer what the image depicts. But in those really narrow shots, it’s as if the image could have come from a sci-fi movie – but it’s still the factory! Playing with scale helps me broaden the vision and subject, to mix those aspects into a wider framework. It comes back to that love-hate relationship again, I want to depict the factory but transform it in my own way.

When you shoot in macro, the camera captures things that your eyes don’t see very precisely, whether it’s dust, the texture of a metallic part of a machine, small ink stains. Those elements become really rich through the printing techniques I’m using; a small metal plate can become a whole galaxy! It’s a nice formal quality that brings something really curious to the work. Something I like to propose in my work is this weird sense of perception; where something’s gained and something’s lost, and where you don’t know what’s digital or painting. I like triggering the viewer to grasp at what they see. It’s also about reflecting on what’s printed in the factory. Those poor materials – stickers, labels – are sometimes absorbed into my work, which sets up a confrontation between a unique piece of art and these everyday materials that end up in a supermarket. Ultimately, both things were produced with the same materials and tools in the same space.

-

-

"I’m not a painter, and maybe I’m frustrated about that! I’m not patient enough, I don’t have the technical skills, I feel totally insecure when starting from a blank canvas." - Jean-Vincent Simonet

GHK: Conceptually, we’re talking here about value, right? That what you choose to enlarge, minimise or distort is also a wider commentary on value, or on this tension between artistic labour and commercial production?

JVS: Yes – to use the space as I did, working with its resources, capturing its image, was about deviating from its traditional function. And it was undoubtedly a way of situating myself within this lineage, of twisting this heritage to occupy a position I feel is my own, and to therefore provoke that tension between different forms of labour, family heirlooms and personal expectations.

I guess I also like this idea of using high technological tools to fuck them up in a way! The materials I print on aren’t at all made for this purpose; they’re normally used to print waterproof labels – for plants, for instance. But when you frame them perfectly and hang them on a white wall, I like that drift between materials, how you can twist their use and context. It’s the same for the things I shoot. When you see traces of what the factory produces in my work, you lose a sense of reality – it abstracts those printed materials in a way.

GHK: In a technical sense, you’re printing on these tricky, disobedient materials: plastic coils used in offset printing, for example. There’s always this interest in materiality and surface in your work; something that’s fluid and in transition. What’s that about?

JVS: There’s a few factors. The idea of a strict, perfectly-produced and framed photographic series is quite boring to me. If a machine can produce the same thing multiple times in exactly the same way, then what’s the point? I guess from a commercial point of view you can sell more, but it feels a bit impersonal to me. I’m not a painter, and maybe I’m frustrated about that! I’m not patient enough, I don’t have the technical skills, I feel totally insecure when starting from a blank canvas. So I use photography as a material, but I try to find ways to escape its reproducibility. Each piece is ultimately unique; even if I were to print the same image two minutes apart, I wouldn’t be able to apply the same gestures to each, nor create the same effects when I rinse them under the water. It’s a balance between having control and inviting new things into the work.I’ve been using this printing technique for five years now, and I’m still not bored. I keep finding new ways of enhancing the approach. I try to create fluidity by unfixing the image, to keep surfaces in a precarious state, like a living organism. After many experiments, I ultimately wash the image, then dry it for framing – or nail it directly on the wall. The final image has remains and traces of those precarious and fluid states, marks of the time and conditions it was exposed to.It’s a combination of elements that creates a kind of surface fetishism. In Heirlooms, all of the images are quite matte – they’re not glossy – so putting them behind museum glass totally disrupts the perception of the image. Just a thin sheet of glass gives new contrast and feeling; it becomes a kind of iPad, it almost seems to revert to something digital! So it’s clear I like to twist the feeling of what you’re seeing. Twisted colours, fingerprints, photographic evidence, dripping parts. There’s lots for your brain to understand!GHK: What does it mean to show these bodies of work together, in one place?

JVS: It’s the first time I’ve had so much space to work with, so it’s a nice way for me to expand the series and show the evolution over the years. Of course, I’m not going to pursue this topic of the factory forever, so maybe it’s a nice moment to combine it in one place. ‘Final’ is a big word, but let’s say that after a few years of revolving around these questions it’s a chance to step back. It does also feel like I’ve been given the keys to the gallery, so it’s nice to think about how to treat the work in the space! The way I work is quite maximalist; I don’t ever like to leave too much empty space, so when I’m given the opportunity to do something I try to give as much as possible – something to really feed the eyes!

The Keys to the Factory is on show untill July 31st at The Ravestijn Gallery. Open from Monday to Saturday from 12:00 till 17:00 or by appointment.

-

-

-

-

For more information on available edtions and prices, please contact the gallery via phone at: +31 (0)20-5306005 or via email at info@theravestijngallery.com

-

Press

-

Young European Photographers, Episode 4: Jean-Vincent (France)

November 9, 2022The documentary series “Young European Photographers” explores the drive behind young photographic creation in Europe. In this 4th episode, in partnership with Paris Photo, Blind meets Jean-Vincent Simonet whose work... -

Meet the psychedelic entities of Jean-Vincent Simonet

September 9, 2018Immerse yourself in the pulsating chaos of the photographer’s images. In Bloom Wanderings through Tokyo nights, a rave in a forest, and countless mistakes eventually add up to emerge as... -

FEATURE In Bloom - Jean-Vincent Simonet

February 19, 2019Jean-Vincent Simonet’s nocturnal trips through Tokyo and Osaka capture wild dripping visuals in motion, its faces and places melting into pools of neon light. The Japan of Jean-Vincent Simonet’s In... -

Paris Photo: Jean-Vincent Simonet, the photographer who erodes the image like a painter

November 8, 2022Young French photographer, Jean-Vincent Simonet makes his family print shop the subject of his latest Heirloom series , like a mise en abyme to better dissect matter and question the... -

Jean-Vincent Simonet’s psychedelic images of Tokyo

December 5, 2018“I love how the city is in perpetual metamorphosis. It’s always moving and glowing,” says Jean-Vincent Simonet, who visited Tokyo, Japan for the first time in 2016, and quickly decided...

-