-

In 2017, Mathieu Asselin (b. 1973, FR/VE) published Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation, examining a history of controversies surrounding an agricultural giant. It was an instant hit, earning him a flurry of awards and widespread international acclaim. With the spotlight, though, Asselin foregrounds the contributions by a host of co-conspirators on which his projects rest, and invites a broader, critical conversation on the scandals he studies – beyond the scope of the photography world alone. With similar motivations and new visual strategies, his ongoing True Colors project tackles Dieselgate – an emissions scandal that rocked the car industry in 2015.

This summer George King interviewed Mathieu Asselin on his latest project True Colors (nominated for the Meijburg Art Commission) which The Ravestijn Gallery premieres at UNSEEN 2023.

-

-

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Audi A3 2011 & C1R - Seaside Blue PRL - BMW, 2023

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Audi A3 2011 & C1R - Seaside Blue PRL - BMW, 2023 -

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Renault Kadjar 2017 & A7/4 - Sueden Metaltico - Volkswagen, 2023

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Renault Kadjar 2017 & A7/4 - Sueden Metaltico - Volkswagen, 2023 -

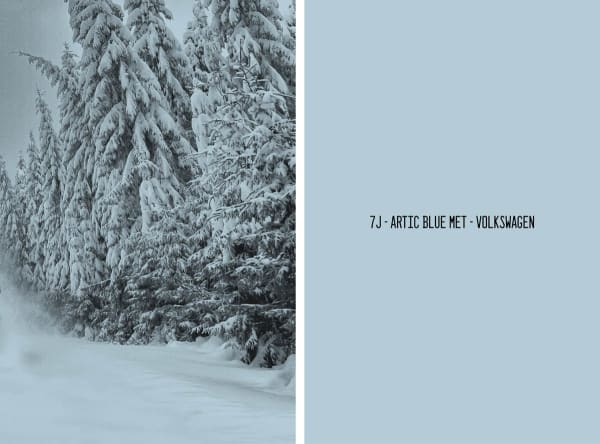

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Jeep Grand Cherokee 2014 & 7J - Artic Blue Met - Volkswagen, 2023

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Jeep Grand Cherokee 2014 & 7J - Artic Blue Met - Volkswagen, 2023 -

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Nissan Rogue 2017 & Y2G - Solar Orange - Audi, 2023

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Nissan Rogue 2017 & Y2G - Solar Orange - Audi, 2023 -

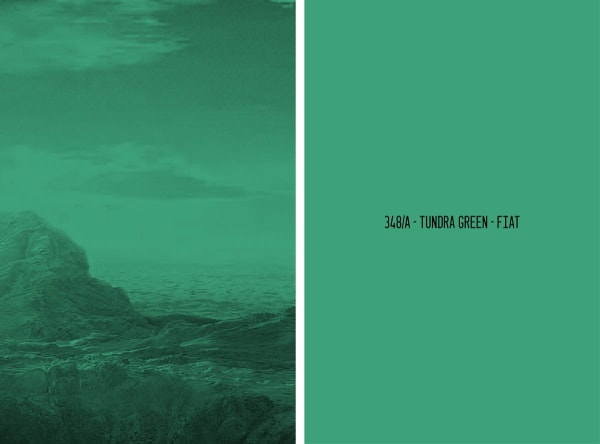

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Audi A3 2010 & 34/A - Tundra Green - Fiat, 2023

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Audi A3 2010 & 34/A - Tundra Green - Fiat, 2023 -

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Mercedes Clase E Cabrio 2017 & B21 - Atacama Yello - BMW, 2023

Mathieu Asselin, Undefined Landscape Mercedes Clase E Cabrio 2017 & B21 - Atacama Yello - BMW, 2023

-

-

-

© Héve Hôte

© Héve Hôte -

-

"I was especially inspired by the work of people like Philip-Lorca diCorcia; I realised that I could handle social issues in a completely different way, with a lot of freedom." - Mathieu Asselin

George King: Straight off the bat, I’d love to know a bit about your background. I know a lot about your work, but less about what went before!Mathieu Asselin: Sure! So I started out in Venezuela, working on cinema production with my godfather, Alfredo Anzola. After that, I worked for about 5 years on film production, then I stopped, and I started rock climbing! It was actually through rock climbing some years later that I picked up the camera again, photographing the sport for different magazines, stuff like that. So that brought me to photography. Of course, after a while I needed to something different photographically – and to figure out what I was doing with my life! I was interested in photojournalism, so I started with that in a sense.GK: And from what I’ve read, you took on a different focus when you were living in the US?MA:Yeah! So I wasn’t very good as a photojournalist for one reason or another – I never felt easy with it – but after I moved to the US, I started to discover more about documentary photography. I was especially inspired by the work of people like Philip-Lorca diCorcia; I realised that I could handle social issues in a completely different way, with a lot of freedom. Importantly, the documentary approach allows you to work with an awareness of your own position, of where you stand in relation to the issue you’re photographing. It allowed me to be more creative, to use different tools. Meanwhile, I became specifically focused on photobooks. I was a founding member of an organisation called 10x10, which started organising photobook meetings in New York. The project grew and the meetings got bigger, so we decided to make it more official. I’m not involved anymore, but the organisation continues to showcase books, develop exhibitions, offer grants, publish. So, I have to say that photobooks were my way into photography; it’s also why I made my first big project in photobook form. -

-

GK: Looking at the issues you’ve addressed throughout your career so far, from the dealings of corporate giants like Monsanto to questions around the HIV/AIDS crisis, and now another environmental scandal in Dieselgate, it feels like there’s a social scientist in you! Where does this come from?MA: I’d say I’m just very curious. I think that’s a family thing. When I was growing up, both my mother and father were very engaged with various different social movements. Women’s rights was one, for instance. My mother worked for a time to help women from Spain and Portugal access abortions in the Netherlands – so I lived briefly in the Hague as a baby. My father’s quite a voice on these issues too; my family was very socially conscious, ecologically as well.GK: Before we go deeper into some of your projects, why photography? What makes this an appropriate medium for tackling these questions?MA: As I always say, it’s not necessarily the best medium for representing complicated issues, but it’s within the limitations of the medium that I find challenges that keep me going. It’s important to say that photography is not enough, at least for the subjects I’m interested in. Despite this, photography still has a lot to offer; there’s plenty to explore. At the core of all my work is the need to say something. Sure, you can go out and protest, or act in accordance with your beliefs in your everyday life. But as a photographer, the camera was a way for me to say ‘this isn’t right, I won’t take it’. It’s a kind of articulated scream. My work doesn’t try to tell the truth – I’m communicating my personal opinions, but they’re fact-based. The Monsanto work, as well as my new project, present a point of view that’s substantiated by research, fact-based research. Photography lets me articulate these things, and I’m lucky enough to have been able to show my work to a substantial number of people – through exhibitions, publications, conferences. Accessibility is another important factor in the way I articulate my work.GK: What about photography’s limitations? Do you end up relying on other media – text, for instance – to communicate your message in full?MA: As I mentioned before, photography alone is not enough. Nonetheless, I’m a photographer. But I believe it’s about utilising whatever I need to tell the story. The text, the appropriated images, the archival material, the design; all of these things are just tools to articulate what it is I want to say. I’m not a writer, I’m not a designer, I’m not an expert in science, so I ask for help from people who have those skills! One friend tells me I work like people in cinema, where a director needs others to animate the script. I’m kind of like that! I can take care of the photography, but I always think about what else I need. Having different people pitch in, collaborating, is helpful. For instance, I work with a curator – Sergio Valenzuela-Escobedo – when making shows with institutions. These institutions already have curators, but we want to have as much control as possible over the story. At the same time, we need feedback and ideas from those in-house curators, because they know the spaces we’re working with. It’s all about collaboration, and trying to balance your own vision with what other people bring.

-

-

"For me, if you can’t translate an idea in a way that everyone understands, it becomes meaningless." - Mathieu Asselin

GK: I also appreciate how you aspire for your message to break beyond the photographic community to a more general audience. I remember that, when you showed the Monsanto project at The Ravestijn Gallery some years back, there was a parallel programme of talks and workshops. That’s quite remarkable in the context of a gallery show!MA:Yeah, that’s really important for me. I love to exhibit in museums or at festivals, but the work needs to be available to other spheres as well. Likewise, the conversation around these issues is something that really goes along with the work. The work doesn’t stop when the project is completed. It keeps on living: when you exhibit, when you apply for grants, when you submit to prizes, when you receive awards, when you publish, when you sell works. Facilitating that conversation isn't only socially-conscious, it’s also very interesting! It’s part of the creative process. How you exhibit in a museum isn’t just about how the works look in frames on a wall.GK: Agreed. Now let’s tackle the Monsanto project, because I guess that’s what most people know you for. There’s something very scientific about Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation. It’s a proper investigation; a very clinical, legal dismantling of an organisation. Why this approach?MA:That’s a good question. I like structures and visualisations. I like things in compartments. I love maps, for example. I like to organise my work in this way. I want to take the viewer on a very structured trip, and I think the fear behind that is in interpretation; we can’t escape the fact that people will always interpret what they see in their own way. It comes with the territory. So I want to be as clear as possible in what I think and say. For me, if you can’t translate an idea in a way that everyone understands, it becomes meaningless. So I take a lot of time to figure out what language I should use, and that’s why having a work that’s organised in compartments – that’s clear in its chapters and documents and photographs – allows me to be more certain about the message I’m putting out -

MONSANTO®

A PHOTOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION -

"I don’t understand when we’re addressing these serious issues, we never see the people behind them. We rarely see names like Monsanto or HSBC or BMW. It’s always a narration of victimhood, pity, atrocities." - Mathieu Asselin

GK: I guess that sense of clarity is also a nice antidote to the hazy way in which a company like Monsanto presents itself to the world, right?MA: Yeah, in a way I’m offering a counterproposal to what Monsanto is proposing, but at the same time it’s important to be clear. Documentary photography is often poetic, and many documentarians want viewers to draw their own opinions on a topic, to feel something when looking at images. In many cases, though, you’re talking about very real things that have taken place, with serious real-world consequences, so you have to be clear. I have nothing against poetry – I use it too! But we have to be conscious of how we’re using these tools. It’s the same with aesthetics. Are we using particular aesthetics for a kind of artistic trip or because it’s the best way to solve very complicated narratives?GK: When issues are so fraught, it sometimes feels like there’s too much at stake to be light and poetic maybe?MA: Yeah! So for instance, I don’t understand when – in contemporary documentary photography – we’re addressing these serious issues, but we never see the people behind them. We rarely see names like Monsanto or HSBC or BMW. It’s always a narration of victimhood, pity, atrocities. It’s probably because it’s difficult to photograph those things at the source – which is when you really need to utilise all your creative tools to show something more, the hidden side of things. To trigger genuine reflection rather than just emotion, you need people to focus on what’s going on. Take ecological issues, for instance. If we follow the science and what the experts are saying, we simply don’t have time to mess around! We need to attack directly! -

-

-

"And here in Europe, nobody went to prison! If you, as a private citizen, did something like that, I don’t know how many years you’d get in prison!" - Mathieu Asselin

GK: Your new project, True Colours, delves into the emissions scandal. Could you outline the scandal briefly?MA: In 2014, a group of researchers in the United States discovered during some experiments that various specific models of Volkswagen’s diesel cars actually emitted much more CO2 in real life than they did under lab conditions. So the US environmental agency took over the case, ran more tests, and confirmed the same thing. They realised that software in the car’s onboard computer was able to gauge when the car was in a lab – plugged into a computer – so that it could change certain parameters in the engine, and the car would pollute less. When the car was on the road, in real world conditions, the onboard computer would revert the parameters. Of course, this discovery was a giant scandal, and it turned out that the technology had been applied to some car models as far back as 2007. Throughout this period, companies advertised diesel heavily – as if it was somehow a cleaner choice. The diesel market grew really big in Europe, but the car companies soon realised they couldn’t live up to the new required emissions standards. Rather than concede defeat, they made an alliance to find another way around the problem!GK: It’s just insane!MA: It is! And here in Europe, nobody went to prison. They did in the United States! If you, as a private citizen, did something like that, I don’t know how many years you’d get in prison! But of course, Volkswagen, Mercedes, BMW, Citroen, Renault, etc., these companies are superpowers, so it’s very hard to go against them. Interestingly, these corporations only have a face when everything’s going well – they’re these solid, wonderful brands. But when things go to hell, they’re faceless, hard to grasp, and everybody starts pointing the finger of blame elsewhere. Who’s responsible for this? It was hard to find out. The companies often excuse themselves by underlining their willingness to change, or by pointing to the jobs they bring to society. Of course, the creation of jobs is one of the most important cards that any politician can play! In politics, you talk about jobs and you can excuse everything. Even if a business is no longer economically or ecologically viable. -

-

GK: And what shape does your project take in a material sense?MA: There’s two main elements to the work, visually speaking. One is the appropriated images of landscapes from car commercials. The second is the colours I’m borrowing from the car industry – the colours in which different manufacturers offer their cars. These colours all have names that are somehow related to nature, like 'White Glacier’ or ‘Blue Mediterranean’. For the landscapes, I’m using an ink created by a team of Indian scientists at MIT labs. It’s a carbon-negative ink; it actually removes carbon from the earth. They’ve developed this ink for serigraphy – so I’m not using serigraphy because it’s cool, I’m using it because it’s the only way to use the ink! I print the landscapes on steel plates, which is the same material used to make a car’s chassis. Before that, they’re painted with a layer of water-based car paint. The serigraphy has a coral pattern, which gives the image a slightly-enhanced photographic quality. Why? Because the appropriated images I’m using are very low quality, so they first go through an AI software to make the image bigger. In that process, they tend to lose some of their photographic quality, becoming a bit more painterly. I wanted to preserve the photographic look.GK: There’s another element too, right?MA: Yes, the other part is about the computer that was installed within the cars. After Dieselgate, the United States ordered the likes of Volkswagen, Audi and BMW to offer their customers the chance to return cars that were part of the scandal. They found themselves with thousands of returns, and they needed to put them all somewhere, so they made these giant car graveyards in many places all over the US. They were found in decommissioned runways, airports, power plants, stadiums. So I gathered all these satellite images from that time of cars in those locations. Meanwhile, I bought one of the computers at the centre of the scandal – the computers that had been installed in the cars to alter the emissions. When I opened it up to photograph in my studio, I was studying the motherboard, and I realised it looked almost like the satellite images of those graveyards. It’s also the reason why the cars are there to begin with! So I made a sort of collage, combining these two separate images into one long narrative of craziness and stupidity!

GK: And what shape does your project take in a material sense?MA: There’s two main elements to the work, visually speaking. One is the appropriated images of landscapes from car commercials. The second is the colours I’m borrowing from the car industry – the colours in which different manufacturers offer their cars. These colours all have names that are somehow related to nature, like 'White Glacier’ or ‘Blue Mediterranean’. For the landscapes, I’m using an ink created by a team of Indian scientists at MIT labs. It’s a carbon-negative ink; it actually removes carbon from the earth. They’ve developed this ink for serigraphy – so I’m not using serigraphy because it’s cool, I’m using it because it’s the only way to use the ink! I print the landscapes on steel plates, which is the same material used to make a car’s chassis. Before that, they’re painted with a layer of water-based car paint. The serigraphy has a coral pattern, which gives the image a slightly-enhanced photographic quality. Why? Because the appropriated images I’m using are very low quality, so they first go through an AI software to make the image bigger. In that process, they tend to lose some of their photographic quality, becoming a bit more painterly. I wanted to preserve the photographic look.GK: There’s another element too, right?MA: Yes, the other part is about the computer that was installed within the cars. After Dieselgate, the United States ordered the likes of Volkswagen, Audi and BMW to offer their customers the chance to return cars that were part of the scandal. They found themselves with thousands of returns, and they needed to put them all somewhere, so they made these giant car graveyards in many places all over the US. They were found in decommissioned runways, airports, power plants, stadiums. So I gathered all these satellite images from that time of cars in those locations. Meanwhile, I bought one of the computers at the centre of the scandal – the computers that had been installed in the cars to alter the emissions. When I opened it up to photograph in my studio, I was studying the motherboard, and I realised it looked almost like the satellite images of those graveyards. It’s also the reason why the cars are there to begin with! So I made a sort of collage, combining these two separate images into one long narrative of craziness and stupidity! -

-

"Work, work, work – there’s no way around that!" - Mathieu Asselin

GK: It’s all embedded in a global framework.MA: Yes. And beyond that, these companies are ultimately selling us a dream of social status and the idea of buying freedom. I’m also making a video for this project using footage from various car commercials, which I’m re-editing to offer another angle on what it is they’re selling. These commercials aren’t even about mobility, they’re literally about freedom and social status!. When they’re shot in cities, the streets are always empty; you never see anyone in a traffic jam! You also never see the economic burden of having a car for lower and middle income households. Could you imagine a world in which all this money was invested in other ways of moving around? We need to remember that – I think it was in the 50s and 60s – the car industry did everything to stop the project of public transportation in the United States. This isn’t a leftist conspiracy theory. It actually happened. Car giants bought up public transport companies and drove them into bankruptcy so they could sell more vehicles. So, if I were to speculate based on history, we should really be questioning the electric car. What will be the next scandal? Will we discover in 20 years that they had another project that was much more sustainable than the one they brought to market?GK: To wrap up, what advice would you give other photographers who are interested in the kind of conversations you’re delving into?MA: Work, work, work – there’s no way around that! But at the same time, if you’re treating these ecological issues, be very sensitive in the way you represent them, and try to understand what our needs are right now. We’ve got scientists calling on other scientists to leave the lab and start protesting! We’re at a juncture where we can’t afford to be soft anymore. I’m not saying we should be violent, but be violent with your art! This is where we need to go. When tackling serious issues, let’s now downplay the way we represent them. -

For more information on available edtions and prices:

-

-

Press

-

Meet the work of Meijburg Art Commission 2023 nominee Mathieu Asselin

July 18, 2023In 2014, a hidden software was discovered in certain models of Volkswagen cars. This software manipulated air pollution tests conducted on vehicles from specific automakers. It was designed to identify... -

‘We need to stop the bullshit’: Mathieu Asselin’s exhausted landscapes

July 19, 2023Renowned for his photographic investigations, Mathieu Asselin now turns his lens on Dieselgate, revealing the car industry’s violent and exploitative relationship with nature. “Now let me ask you a question,”... -

Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation

September 14, 2016Hard-hitting documentation of the countless communities dramatically affected by the unscrupulous policies of Monsanto®—this reportage reveals the toxic legacy of one of America’s most controversial corporations. The multi-multi-billion dollar agro-chemical...

-