Tucked into the endpaper of an issue from MATTE Magazine, there is a small, black and white self-portrait of Michael Bailey-Gates as the devil.

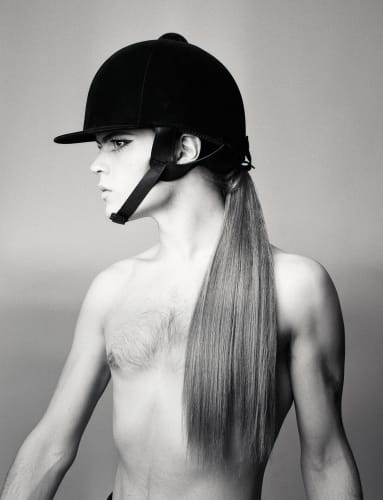

Dressed for a funeral in suit and tie, his lips are painted black with wide-open eyes staring straight out at you beneath cartoonish horns. Although this is one of his more straightforward concepts, this is one of my favorite pictures from Michael. It shows one of the many vaudevillian roles he plays both in front of and behind the camera—devil, provocateur, magician, clown, acrobat, juggler, ventriloquist, strong man, trick pony. As the curator Horace Ballard wrote in Michael's issue of MATTE, “With these photos, I’m not just unconcerned with reading the gender of the bodies before me, it’s also futile.”

In Michael’s personal work, he creates a world where roles are fluid, and he and his friends and people in his community play all the parts interchangeably. Everyone is both hero and villain; all are both muse and musing. His work doesn’t deny the question of gender, it simply makes it seem superfluous.

Wherever Michael’s work actually takes place, I think his process is one of creating a space where many of the borders and hierarchies and defined limits of daily life can disappear. And he does it through joy, which has always been the most impressive thing to me. I am not someone who is always interested in seeing depictions of the joy of life, because usually, that kind of image is trying to sell us something. However, Michael uses joy to sell us his own subversive messages; he uses joy as a tool for revolt.

I’ve asked him about the devil and it turns out he has done multiple self-portraits as Lucifer. “It represents mischief,” he told me. Maybe mischief is the best word for his singular combination of play and provocation. If so, Michael’s work is serious mischief.

Michael: Yeah, I went there originally when I was 15 for the pre-college program—I did a color darkroom class. It was before SVA ripped out all of their color darkroom stuff. I think they were one of the last schools in Manhattan that had them.

Michael: So I went there for that class and some of the people I met then are still my friends now, like Brooks AdaLioryn who is an artist here in Los Angeles. I joked that the SVA pre-college kids figured out how to politely run away to New York [both laughing] because to do that to my family was unrealistic at the time.

Mo: How did you communicate to your parents, who were science teachers, that this is what you wanted?

Michael: A lot of high school was figuring out how to get what I wanted without hurting people. [both laughing] The fantasy of just getting up and running away to New York would have hurt my family—it felt like a classroom daydream.

Mo: Did you have peers or friends that had that same fantasy?

Michael: There were theatre friends wanting to go to Broadway—I was in a self-conflicted world then to begin with. [both laughing] I imagine It was a scary thing for my parents when I decided to move to New York with people I met on the internet. Nothing really came up in a way that was comforting except for the institution of school. That was my not so clever trick.

Mo: What did you realize once you were able to go to SVA?

Michael: God... I realized I was going to be in so much debt. [both laughing] If I were to do it again I would have just done it by running away. I wish I had been more courageous then.

Mo: Well, what did it reveal to you about yourself that you didn’t know at the time?

Michael: I think of New York then as a place that brought out whatever demons I had and I had to run into them and just get over it. I loved that, and there was a lot of it. School was good, but the things that come back now that are important are the relationships and experiences I had outside of school. Rebelling against a school institution, especially having grown up with two teachers, was very personal.

Porch, 2018

Mo: What do you want to extend your practice towards after being so formalized in photography?

Michael: Well, it was realizing that my message can stay consistent regardless of the medium. Whether it’s performance art, which I did for a while, [laughing] or painting.

Michael: It’s a little off topic but my friend Leah James, a photographer and performance artist, worked a lot with Flawless Sabrina, this amazing pioneer performer that basically organized drag in the U.S. and got arrested countless times along the way. Towards the end of Sabrina’s life, Leah organized a talk at SVA and in my more confident academic language at that time in school I asked, “What’s the job of a queer artist?” and Flawless Sabrina, who was very old, sort yelled at me. [both laughing]

Michael: I’m trying to remember the exact words, but she told me to stop labeling work under the umbrella of “queer” and to just make the work. I felt a pressure go away to hear that. When you just do it, what you have to say comes through regardless.

Mo: Do you feel using the word “queer” gave you a sense of safety?

Michael: I think art school is a funny time. It’s a lot of people all learning who they are. Then everyone is getting into the process of making work... It was group therapy, so it kind of happens—

Mo: —through a label?

Michael: Yes! I feel like Flawless Sabrina, for me, broke that and was saying, “Snap out of it. Just make it.” It doesn't really matter who you are or what group you fit into, what you want to say will come through.

Mo: What do you feel like your practice has revealed to you lately?

Michael: My favorite work happens when I’m playful and not so serious about it. It’s full circle, because when I was doing my thesis at school, I was working with revolting through this idea of what joy is. I lost that joy after because I had to hit the ground running after—I was taking it too seriously.

Mo: What cities or places in the world do you have an emotional connection to and why?

Michael: I’m realizing New England was influential to me… I had rejected it and now that I’m away from it for so long I feel that witchy darkness is something that I crave sometimes. I notice when I’m looking out the car window and see buildings I’m thinking , “Oh I love that house.” I think about why and I realize it’s because it’s old and falling apart and reminds me of New England. [both laughing]

Michael: Anywhere that’s falling apart is a space I’m more at home at. My friend Silvia Cincotta has done hair and makeup for many of my shoots, and she was kind of my older sister moving to New York. Her apartment building was where I had my studio for three years. That whole building, 185 East Broadway, was just bought and is getting demolished. It’s this beautiful old brick building that really was falling apart so maybe it was it’s time...

Mo: Was it falling apart when you lived there?

Michael: Oh yeah, not to mention the rats. The landlord was poisoning rats when I was in there. I built this set with classic clouds and green grass—that kind of thing—and this rat crawled to the top of it all drugged out. I had to kill it with a frying pan, but I love that building. I’m sad to see it go.

“Finding people who have similar songs or something to say as you do makes it easier to jump in and hold the melody. — Michael Bailey-Gates

Candy Magazine, 2018

Michael: It's strange. I didn't realize how dark LA is. LA’s very pretty but there’s always some story or death behind everything. [laughing]

Michael: Sometimes when I’m in New York, sitting at a restaurant with my friends, I just wish I could be in a more intimate setting for longer, and houses feel like intimate environments. So for me, it's revealed that being in a house can be more beneficial for making work.

Mo: Was that a conscious decision or something that just happened?

Michael: It just happened. LA has shown me that stepping back is helpful for me to make work.

Mo: What has that disclosed in your work?

Michael: It’s made me think about how much of my personal life I include. My friend had a baby recently and she’s always having him on set because she’s a stylist. I asked her and her partner if I could pose with their baby, Fox, in a photo of me with fully done up makeup and hair.

Michael: Having him on set was really fun and he was having a good time, and then as soon as we went to take the photo, they turned on the wind machine for my hair and Fox just started wailing. He didn’t like the noise. We were just like, “Let’s get the shot after he calms down,” and put him back on my lap. Every frame was me with this wailing baby and I guess that was kind of the answer to my question. So looking at those pieces, LA brought me to those pictures.

Matte Magazine, No. 53

Mo: What did New York reveal in your work?

Michael: A grounding idea for my work is everything has something to say. When I’m in New York I see that message clearly. Finding people who have similar songs or something to say as you do makes it easier to jump in and hold the melody.

Mo: How have you learned to find those people?

Michael: It happens naturally. With friends I believe I have to let people go and do their own thing—I’m not a person who hounds others with a friendship. I think you just do your own thing, say what you have to say, and eventually people you really love just kind of enter your life.

Mo: Is there a genre of beliefs that you find yourself gravitating to? Or at least gravitating to within your friendships?

Michael: I can be spiritual with my work, and for people who make work in a similar way, that meet up just happens.

Mo: What have you learned from it?

Michael: I’ve learned how small my bubble is. Going back to that photo with the baby, actually. Matthew Leifheit put that picture on the cover of his publication Matte Magazine. I had a signing at the LA Art Book Fair, and I remember getting up to use the bathroom and I sat back down and Rachel Stern told me that this guy came up and was very angry about the poster with my photo on it. That guy later found me online and sent me these cryptic memes. I did a piece with The New Yorker, too, and when they put it up on their Instagram I had weeks of these intense messages.

Michael: Rarely does my friend bubble pops for me... [But] that tiny bubble became smaller quickly. I had strangers telling me, “We are gonna come find you and string you from a light post.” There were a lot of visual messages.

Michael: Some viewers saw the baby crying as a reaction to me being visually “other.” But not because babies cry all the time. So it was these messages of being, “Oh, your queerness makes this baby upset.” It was interesting to see people projecting those views onto the photo.

Mo: What always interests me is that challenge of realizing where your work exists within the bigger picture. It forces you to bring that narrative to more people. What’s also interesting is that it takes more energy to talk to the people who have different beliefs from you than the people you’re naturally comfortable talking to.

Michael: Yeah, I have a curiosity for people who are different then me with their beliefs and that gets me into trouble. [both laughing] So clashing with people, I’m like, “Oh god, I have this love for your passion.”

Mo: But you're empathizing, you're trying to see through their lens.

Michael: Yeah, and it’s hard because, well, especially in “Trump America”, I get it but I absolutely don't.

Mo: Of course. I was just in Packwood, Washington for a shoot and it reminded me how insulated these metropolitan cities we live in are.

Michael: Yeah these progressive bubbles—bringing up New York and LA—I can see similar people more easily. But you're forced to challenge that way of thinking when you leave and go somewhere like that town in Washington or to a visually more conservative environment. It takes much more effort to be authentic for me in those places.

Mo: Most art exists in these progressive cities if we’re being completely honest, so who are we really vocalizing the work to? Maybe we’re just talking to ourselves. It’s great if there’s a space sharing often silenced ideas, but how do you mention that same idea in the “other” playground?

Michael: It makes me think of the artist Avram Finkelstein. He made the Act Up silence=death symbol. He did this interview about academic conversations where he said something to the effect, “How do academic conversations apply to somebody who drives a cab for a living?” And his answer was like, “I worry that the language alienates the very people those conversations are about.” I now think of that too when thinking about conservative spots. How is what we're communicating being received by somebody in our country who may feel so alienated from what we’re doing as artists?

Mo: How do you feel that conversation lies within your work, if it does?

Michael: I make my work with close friends and with my teams. It’s a lot of fun. I’m making these pictures without any fear, which is very freeing at that moment. But after, when I’m presenting myself, I’m not always in the same embodiment of when I was making the picture.

Mo: Do you try to connect those worlds or do you just let them exist in their own sphere?

Michael: I’m not as great as talking about work as I think I am about…

Mo: Creating it?

Michael: Not that I'm great at making it, [both laughing] but I feel more confident in saying what I have to say through a picture than I do through my own voice.

Michael Bailey-Gates and Bryce Anderson for Beauty Papers, 2020

Mo: Who have been some of your perceived heros in art? Or simply, people that you just resonate with a lot?

Michael: I think of Lisa Yuskavage and Kara Walker. I remember when I was living on Cape Cod and working at this deli, I would go to the library on my days off, and one day I read this article on Kara Walker. She had a great way of describing her own work. She said, “There’s no hero and no villain,” in her work. That’s always stuck with me.

Mo: It’s interesting that you gleam reverence through painters. Inspirations don’t have to be so direct, you can find their neighbors. As much as I love photography, I don’t read many photographer’s interviews. I’m interested in the birdseye view of it since I never had a formal education in photography.

Michael: Yeah, but I don’t think you need it. [both laughing]

Vogue Paris, 2019

Michael: I don't think formal education does a whole lot—what you're doing interviewing people in our industry and the work you put in resonates with me.

Michael: I modeled for a while and I got to shoot with a lot of photographers that I admired. Internally, I’d try to be quiet about it. But really I was feeling, “I can't believe this is happening.” To be able to sit down and interview, like you do, I think would be the best education a person can get.

Mo: I mean, having that nervous energy in terms of meeting those people helps, right? That nervousness can put you in a vulnerable and intuitive headspace. I sort of self-sabotage myself in a few ways with every interview so that I’m fully present. To paint a visual for those reading, you and I are sitting at this table in a cafe in our neighborhood and I have no notecards—let alone, no preliminary ideas of what we could’ve talked about.

Michael: Oh yeah, I think that lets things happen more naturally.

Mo: You become wholly present. Are you a present person?

Michael: Umm, no. [both laughing]

Mo: So you look ahead?

Michael: Well, right now there’s so much talking about taking care of yourself, or the idea of being grounded or present. I was seeing this healer for a while and when I was talking to her she asked me what I was seeing. I would frequently see this angel tied to a tree and it would be struggling flying in the air and it had a rope with a bloody ankle. I thought it was stuck. I realized the rope was trying to help her, or it was this visual of being grounded. I am floaty, but also with getting older I’ve learned to be happy for the things that keep me here.

Mo: For sure, you don’t have the energy to jump as high as before, but that's the beautiful thing about youth. It might let you reach that point easier. The duality in that idea is that youth might distract you from that ability, so it might be more straightforward to reach that point when you’re older.

Michael: I’m trying more to get rid of the idea of the classic timeline of human life where it says at 20 you should be doing this and at 30 you should be doing this. There’s people who have had to be a teenager when they’re 50, or it’s the opposite. I hope that as I’m getting older I’ll go through periods where I’ll have huge bursts of energy still. [laughing]

Love Magazine, 2020. Styled by Ib Kamara.

Michael: Now, I’m more interested in an artist who’s in their 60’s and just starting and they’re really hitting something magical for them.

Mo: I agree. A lot of people will glorify the kid who’s in their early 20’s, but that person hasn’t had that much time to form as a human, let alone absorb certain nuances of a career you can only learn through time, redundantly, through decades. The gradual journey is an investment in longevity. That’s the space I like to flirt with. Do you think about longevity?

Michael: Sure, but I don't think you get to decide when you get a spark. When I’m trying to force something, it’s not always as genuine. If I’m like, “This one has to be the best one,” it’s usually not . So in terms of longevity, it’s about being more open to all possibilities, you know?

Mo: Have you always been open to possibilities or did that take some time to learn?

Michael: I think I'm more of a thrill seeker now. [both laughing]

Mo: In what ways? Are you looking for something that will make you as uncomfortable as possible?

Michael: I think it’s more of the, “I’ll try anything once,” attitude now while working.

Mo: Do you feel like that parlays into the purpose of your work?