Houses and their inhabitants have become one. With Covid-19, our homes are no longer somewhere we leave and return to, they are the places we stay — unceasingly and indeterminately.

Long before the pandemic, however, architecture and humanity would blend at Ponte City — the infamous cylindrical skyscraper rising 55-stories up in a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. The mammoth structure wraps around a hollow core; a dystopic vision of row upon row of apartments circling upwards above an uneven rock floor. A dysfunctional concrete cylinder brought to life by its residents — a modernist architectural fantasy gone wrong.

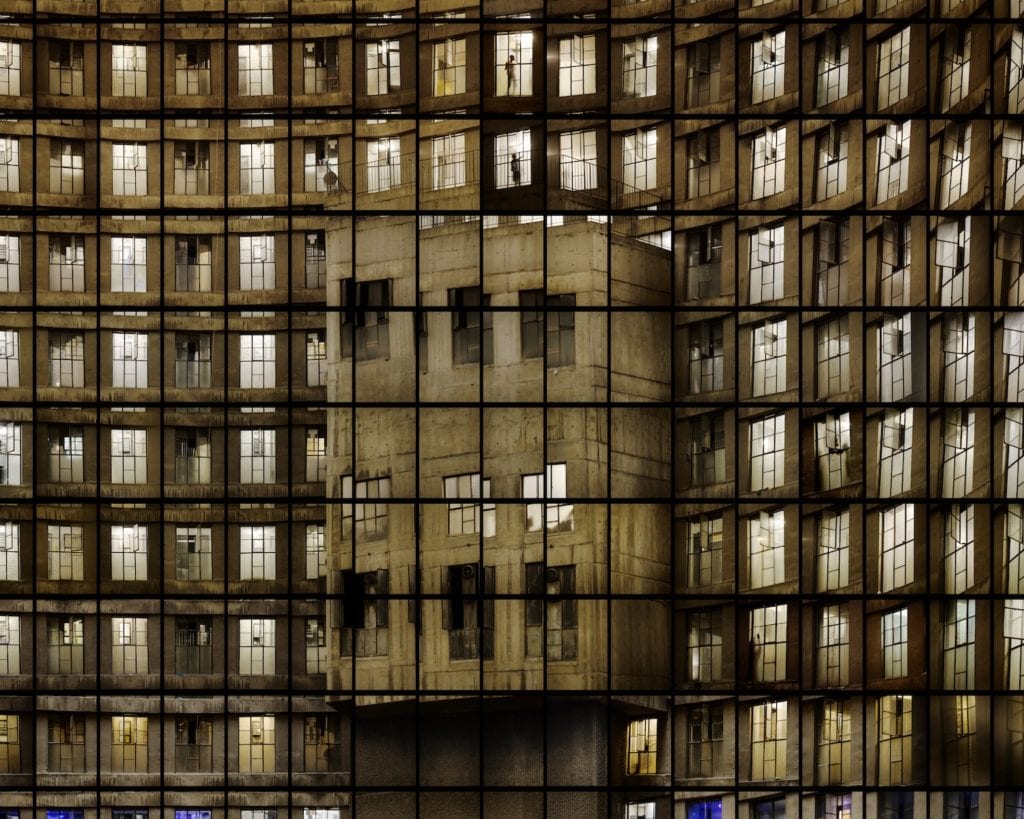

In 2008, South African artist Mikhael Subotzky and British artist Patrick Waterhouse began a project about the building. The undertaking would span six years. A mysterious quote, supposedly from the modernist pioneer, Le Corbusier, played a large part in shaping their approach. It observes that the essence of modernist architecture resides in a building’s apertures: the openings — the windows, doors, arches — of a solid structure. And so, the pair set about systematically photographing the apertures of every apartment in Ponte City: the front doors, the outer windows, and the buzzing television screens — three distinct apertures catalogued into three different typologies, each of which the artists present in three different ways — via individual photographs, projections, and four-metre high lightboxes. First exhibited in 2010, the three lightboxes were arranged to mirror the structure of the towers — composing every front door, and every outer window, and every television screen — golden light melting through the relentless repetition of the building.

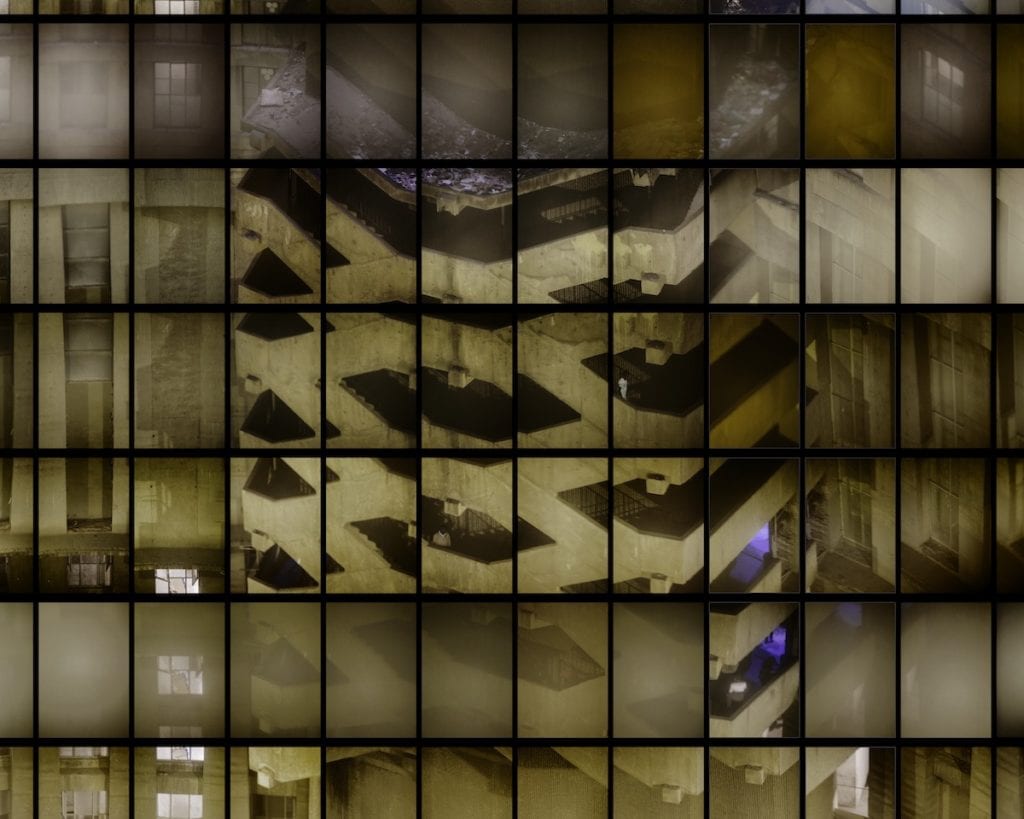

“What better way to echo Ponte City’s brutalist architecture than to apply the principle of typology,” observes Clément Chéroux in an essay included in the second edition of the book. The publication, long out of print, has been revised and extended to accompany an upcoming monographic exhibition of Ponte City at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), now postponed until 2021, to mark the museum’s recent acquisition of the work, which comprises photographs, texts, and found documents. In the interim, however, a recent addition to Ponte City is on show at Goodman Gallery’s virtual viewing room at Frieze New York, which runs from 08 to 15 May. The additional element, or as Subotzky puts it, “the unwanted child”, comprises a fourth and more complex typology, which the pair were reminded of when revisiting the work for the new publication, “it is the last part and it has never been seen before,” he continues.

This last part encompasses the interior passage windows that enclose the gaping, hollow core, which runs almost 200 metres up Ponte City’s centre. Subotzky and Waterhouse photographed across the core on each floor, pointing straight over the 30-metre abyss, but also up and down to capture the vertiginous scale of the space. The images are obscure, a result of the darkness in which they were taken, along with the filth and grime clouding the locked corridor windows through which the pair were often forced to shoot. Bursts of colour and flickerings of life, do, however, punctuate the otherwise overwhelming emptiness: a man has cracked a window and gazes out; a family congregate in front of a clouded pane of glass; an onlooker presses his face to an aperture and peers through it.

“Ponte City is emblematic of all of those failures, but I guess it has become something else — a kind of beautiful humanity”

At first, the pair debated whether to avoid including people in the frames. Their presence was interrupting the artists’ regimented documentation of the structure. Ultimately, however, it was out of their control; the inhabitants of Ponte City took over. “We removed the concrete of the modernist architecture leaving us with the apertures,” explains Subotzky, “and the apertures have a kind of purity to them, however, what is most defining about them is the people – the people who have put curtains up over their windows, the people who want to pose in their front doors, and even the people populating the television screens”.

It is that tension, between the purity and stillness of the architecture and the vivacity and chaos of its residents, which symbolises Ponte City’s essence, but also its failure to become a modernist miracle — some arcadian city in the sky. And, in the context of South Africa, it also represents a second failure: the failure of apartheid, which Ponte City once symbolised. When the structure was built in 1975, the neighbourhood surrounding it, was exclusively white and the residence was envisioned as an apartheid-era model for optimum living. Thankfully this was shortlived — the failure of apartheid saw both the area and Ponte City become increasingly integrated.

Gradually, however, the building deteriorated; by 1994, it was regarded as an emblem of crime and urban decay, a reputation that is not entirely accurate and which it has struggled to shake. In 2007, developers bought the building and the re-development project New Ponte was put in motion. They evicted half the tenants and began building what was planned to be a shining showpiece of upmarket, cosmopolitan living, but, the 2008 financial crisis and the recession that followed halted the renovations, which eventually fell apart. The fantasy of a revitalised Ponte City had also failed, and Subotzky and Waterhouse, who had moved into one of the showroom apartments, decided to remain and explore the layered histories of the place. “Ponte City is emblematic of all of those failures,” says Subotzky, but I guess it has become something else — a kind of beautiful humanity.”

And despite its tumultuous history, Ponte City remains populated — a place that thousands have passed through, usually staying three years at most. “It is difficult to live there,” says Subotzky, “it’s breaking down; it’s intense”. The cylindrical structure is secondary to those who have inhabited it — a container for their stories, histories, and lives, however, at a time when Covid-19 has relegated us to our homes – isolated and locked down – it is difficult to look at the lightbox and imagine the individuals confined to Ponte City. Abandoned within an architectural dream, which has failed to serve them. ”I guess that is the thing about Covid-19, this time is a great opportunity to reflect on things but it also exaggerates class and race divisions,” says Subotzky, “It is hard to think about Ponte City – it can’t be an easy place to be locked down.”