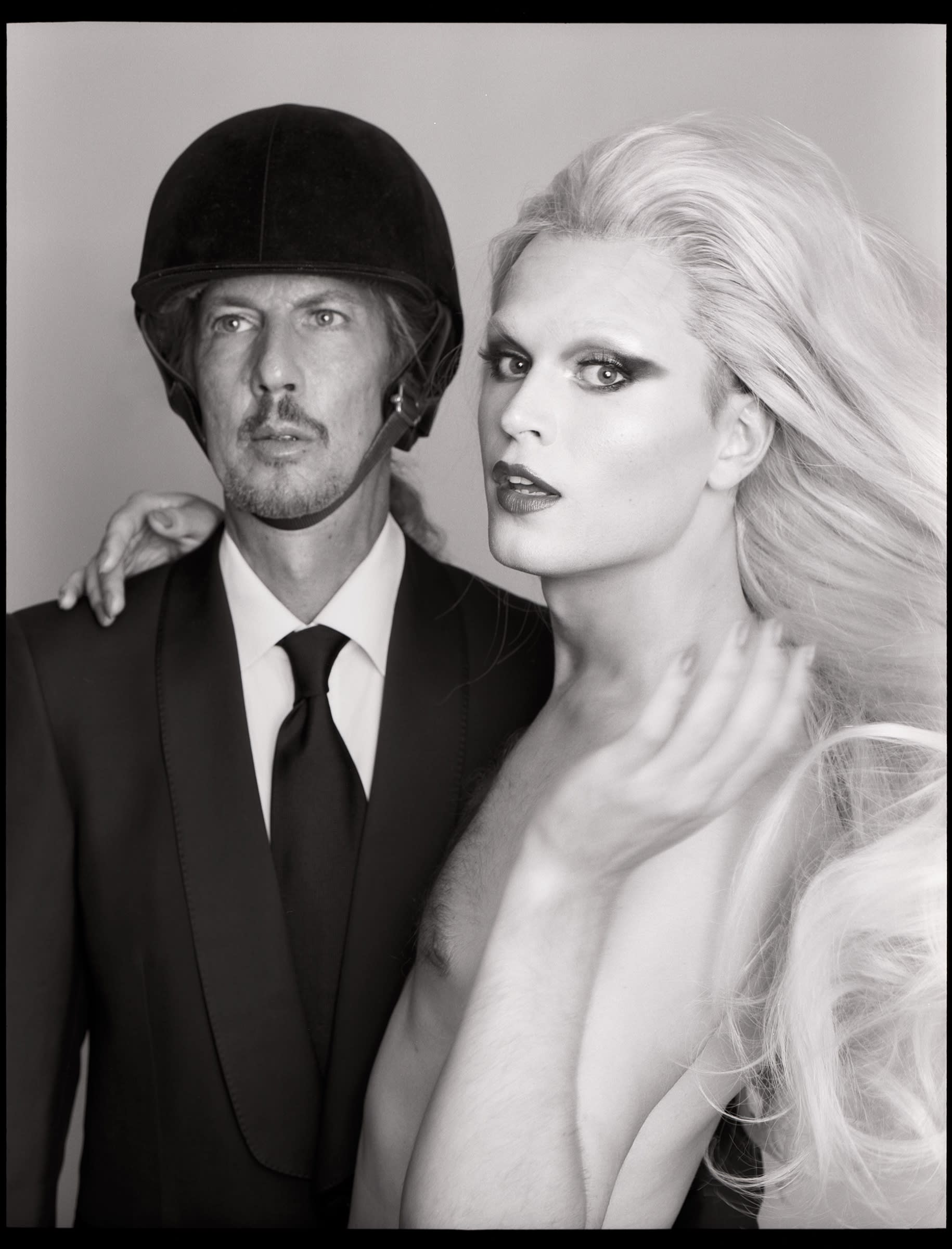

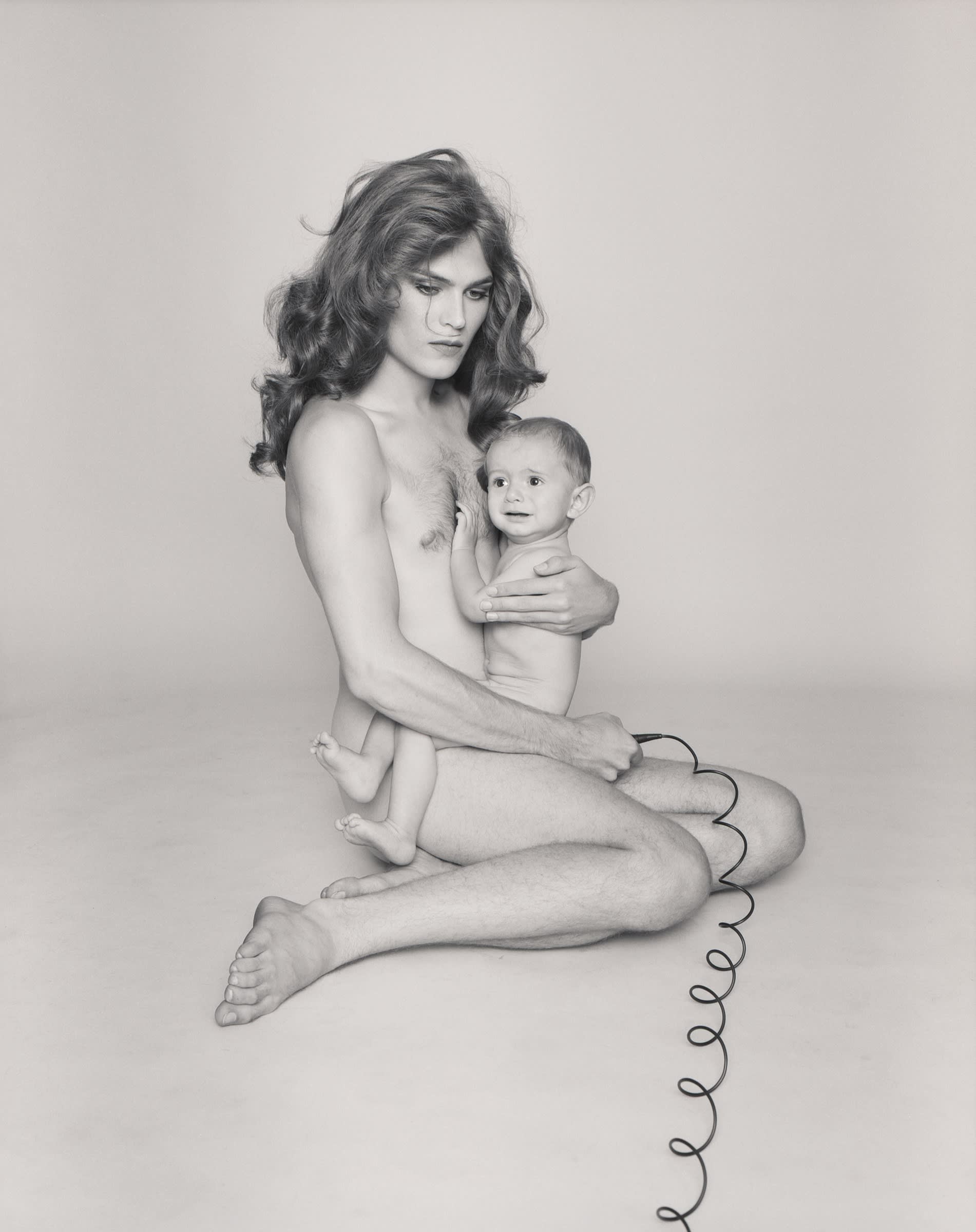

As the dark side of the moon has always been so alluring and mysterious, sometimes those very mysteries and secrets are hidden in plain sight, or perhaps — in plain light. “A Glint In The Kindling” is exactly that: Michael Bailey-Gates’ exhibition, held at Ravestijn Gallery in Amsterdam, and his upcoming book are a collection of pictures whose starting point is always the light. It’s that kindling that allows us to leave our imprint on this world before we set it alight through our uniqueness; we consist of layers and multitudes of ways of being, after all — nothing and everything, all at once, starting from gender and subsequently stretching beyond that. We are limitless and Michael Bailey-Gates isn’t afraid to say it out loud.

DANIELA MORPURGO. How did you first discover photography?

MICHAEL BAILEY-GATES. I’ve been doing photography since I was a teenager. I found a very tight-knit group of people online who I’m still friends with. We keep in touch and we’re all really supportive of each other. That’s something that has little by little been becoming more serious to me, realizing that I could make a career out of it. So I really started at a young age, and then I tried a lot of other things like video work, painting, performance art, and a lot of other mixed media. Eventually, I kept swinging back to photography and so that really told something about myself.

D.M. Do you tend to use it as a means to portray reality as faithfully as possible, or do you like channeling your own ideal imagery in the pictures you take?

M.B.G. To be honest, I feel like I’m constantly stumbling through it, tripping over myself. I’m a photographer, but firstly, I love pictures and everything about them is magical to me; their ability to predict and unearth secrets. And it’s very dark and really defies logic to be able to take a piece of what’s physically in front of you, manipulate it and then call it “truth” — is there anything more awful or mysterious than that? I think photography is the only thing that people really believe as truth.

D.M. Your pictures are distinctive almost in a theatrical way. Is it how you give another, alternative perspective on gender-related subjects?

M.B.G. Yeah, definitely. I think it’s for that whole world. It’s really about holding both, but eventually, being our own selves is the only truth we can speak about. Everything else is a wild guess. Also, when I’m really connected to someone and I feel like I can see their limitlessness, I think it helps kind of push those boundaries of reality.

D.M. Your upcoming exhibition in Ravestijn Gallery is “A Glint In The Kindling.” Is it inspired by Robin Williamson’s folk album, or is there another reason behind the name?

M.B.G. No, the name actually came to me by chance — the definition was something like small flashes of lights and reflections. The title “A Glint In The Kindling,” for me, is akin to the fire starter; it’s the beginning. Moreover, those flashes of light create a picture. There’s this idea I learned in school that’s always stuck with me: when you leave a water glass on the table, it leaves a watery ring behind and that’s actually considered to be a photograph because it’s an imprint of itself. I love that photography leaves behind this imprint of ourselves, even if it’s sloppy and exaggerated at times. So, going into the kindling, it reflects that it’s this imprint of us, of my close group of friends, who are all part of this book and my body of work. So, that precise moment in time is what the kindling represents for me.

D.M. Kindling is also reminiscent of another word, a largely used one at that: triggering. Does your photography also express your own triggering moments and epiphanies?

M.B.G. Photography has always felt a bit forbidden. I don’t know if it’s particularly like a trigger but there is always a sense of mischief, a sense of doing something wrong while being able to get away with it by making my work sometimes. And I’ve learned to love that and not be bitter about it. I think this body of work has this powerful punch to it. So, I can see that there’s a sense of a push to it, you know?

D.M. A triggering reaction was also the one you got with the self-portrait you realized for the Valentino bag campaign last spring. Why do you think people felt so triggered in a time when we are actually quite used to seeing diversity and gender non-conforming bodies in media and social medial especially?

M.B.G. Yeah, that was a funny one. I can only speak for myself, but I’m so happy to be in my own little world, my own little bubble, wherever that may be, and whatever city I go to. Being more specific about that, there’s a sense of safety when you’re just with your friends or in certain areas of the city that you’re most likely fine to be in. And I think that reflects on the Internet as well. We’re really all in our own little bubbles on the Internet. And when those bubbles pop, we see that there’s a whole different world out there; there’s a whole country in-between New York and L.A. That was kind of a forceful reminder. And that happens all the time for everybody who is part of other smaller realities. Those perspectives of negativity are not gone.

D.M. As sociologists like Zygmunt Bauman theorized in the past century, we all live a liquid life, and therefore, our identities, and sometimes gender identities, in particular, can’t help but be fluid. Do you think your work is contributing to expanding the scope of what we perceive as normal? Is it something are we socially achieving to understand?

M.B.G. Yeah, I think there’s a perspective emerging of holding both, or at least more than just one, flat, univocal identity, even though the philosophy of holding both is really difficult; and that’s not just for gender. Gender is almost secondary. It also comes up at work or in your day-to-day life; everything is not black and white, it’s not left or right. Everything can be both instead of either/or. For me, for my growth as an individual and in my art, it’s really difficult to abandon that philosophy of not making things black and white. My personal goal is to allow my friends, and everything and everyone I cross my path with, to have that limitlessness without fitting my own expectations on other people. It’s really difficult and yet really powerful. It’s a process and I’d love to go beyond seeing things through consolidated boxes and categories. We are more than one thing, we are everything and nothing at once

D.M. Most of your pictures seem to be black and white. What is the reason behind that choice?

M.B.G. I do have a very restrained use of color sometimes. I think, right now, or in this past body of work, black and white have felt really comfortable, and it also feels very timeless and speaks to a big chunk of photography. To be honest, I don’t think about it a whole lot. But, I go through phases where it’s color only and I go through phases where it’s only black and white. You just kind of feel it in the moment, and it’s a project-to-project thing.

D.M. How did you get into exploring gender expression, especially in relation to your own image? Has it anything to do with fashion, too?

M.B.G. There is this artist in New York, her name is Kembra Pfahler, and I used to assist and work with her. It was really formative because she introduced this concept called “availabilism,” which is basically just working with what’s around you: it is something we all do but it also made me feel grateful for what I have. I don’t like to call my work self-portraiture but I use myself just because I am the first person available when I want to shoot, and also because, again, the only veritable truth I can speak of is my own, so, eventually, I am in the picture and I am the picture.

D.M. Have you ever had an inspirational artist who also uses their own image to make statements, like Sherman, Abramovic, or Woodman?

M.B.G. I know Francesca Woodman’s work intimately. She was from Providence, R.I. where I also grew up, but have always felt more attracted to my relationships with others and the possibilities of the self that emerge through those relationships.

D.M. “A Glint In The Kindling” also leads to thinking about a new sparkle of light and a new beginning started by flashing lights. Is there something, in particular, you’d like to see starting in the future?

M.B.G. Yes, it’s more of a food for thought. We can’t make pictures without light and I tend to be awful about how I view my place in the world. Yet, we keep forgetting we are young and we have so much time. I’m thinking about looking back at these pictures in 20 or 30 years’ time and seeing the different meanings they’ll have. That’s the magic of photography; predicting and unearthing things.

D.M. Are there any artists you’d particularly like to work with?

M.B.G. There are so many artists I’d love to work with, but after almost two years living with COVID and being limited without seeing people, my photography heaven would just be staying in a big house with the people who I feel closest to and just working together. I miss that so much and it’s slowly going back to that little by little, so that is where my mind is… Ok, maybe not in the same house but let’s just say a campus — a photography campus.

D.M. Do you ever feel influenced or that you are straying from your own art once you come in close contact with another creative mind?

M.B.G. I think it’s like a big, juicy part of all of that. You know, it’s not one specific thing. I think for me, it’s really this kind of big soup where everything is mixed together — it’s difficult to describe. I think there are good days and then there are bad days.

D.M. What do you do when you have bad days?

M.B.G. I was talking about this with my friends the other day and I think you don’t have to do anything. When you are not inspired, it’s just a moment of rest; the idea will come in another moment. It comes in this burst and I am like, “How do I make this happen right now?” But it’s not always realistic, just sometimes — sometimes I’ll go down to my little workshop and start chipping away. It’s about keeping the enthusiasm from when I have that spark and carrying it to the finished moment. It’s always a challenge, especially adjusting to the COVID world, where there are lots of hoops to jump through right now.

D.M. Do you ever feel like Dries Van Noten, who cannot see the real version of his initial ideal inspiration in order to keep his creativity flowing?

M.B.G. I don’t know about that, but it reminds me of a friend who is no longer with us. She was super sensitive and she wouldn’t go to certain exhibitions not to contaminate her imagination. Someone in Japan once told me about the “Paris Syndrome.” Basically, it is when you find something different from what you expected, and maybe Paris is not as decadent as we all like to imagine it [to be]. It’s a game between expectation and reality. Reality always comes after you imagine a place without actually experiencing it.

D.M. Are there other projects in the making besides the exhibition in Amsterdam?

M.B.G. Yeah, definitely. I am working on another book after this, which I hope will come out quicker, as well.