“3D printing will play a key role in extraterrestrial architecture,” explains Ersilia Vaudo, who nails me to my chair with a fiery glance when, in a Starship Troopers teenage overdose slip-up, I ask her for more details about the “conquest of space”. Vaudo is an astrophysicist and the Chief Diversity Officer of the European Space Agency, as well as the curator of “Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries”, the exhibition that acts as the “nerve centre” of the 23rd International Exhibition at the Triennale. “We are talking about inhabiting, not conquering,” she graciously corrects me.

Amidst cannibal galaxies, extraterrestrial architecture and 3D printers that “fix” astronauts, astrophysicist Ersilia Vaudo leads Domus to the frontiers of space exploration through the exhibition she curated for the International Exhibition at the Triennale, “Unknown Unknowns”.“3D printing will play a key role in extraterrestrial architecture,” explains Ersilia Vaudo, who nails me to my chair with a fiery glance when, in a Starship Troopers teenage overdose slip-up, I ask her for more details about the “conquest of space”. Vaudo is an astrophysicist and the Chief Diversity Officer of the European Space Agency, as well as the curator of “Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries”, the exhibition that acts as the “nerve centre” of the 23rd International Exhibition at the Triennale. “We are talking about inhabiting, not conquering,” she graciously corrects me.

The title was inspired by an important passage in a psychological study from the mid-1950s, which became extremely popular during the Iraq war thanks to a linguistic mess by US Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld, who said something like “as we know, there are things we know, we also know there are known unknowns”. Vaudo loves the ambiguity of the chosen title - “a weapon of the unknown”, as she calls it - because it can be both interpreted as “the unknown unknown places” or as “the unknown person who does not know”. And she points out that Rumsfeld has nothing to do with this.

To explain how she, an astrophysicist, arrived at the Triennale, she goes back to a few days before Covid-19 became a global pandemic. Coincidentally, it was a talk entitled “La prima volta” (“The first time”) that led her to this debut. Vaudo was participating upon the invitation of Stefano Boeri, the president of the Triennale, and a key passage of that talk was that we only know 5% of the universe. The theme of the unknown - shared by many of the experts there - was amplified by the unknown guest knocking at the door, a virus about which we knew very little at the time. “I said to Boeri, why don’t you do an exhibition on the unknown?” says Vaudo. And so, here she is, curating that exhibition. “For me, it is an absolute first, I come from different worlds,” she says.

An astrophysicist at the Triennale

In the temple of design in Milan, Ersilia Vaudo is almost an alien sighting. She seems to come from an extraterrestrial orbit, just like the things she puts on display. A pleasant talker, she is capable of quoting Leibniz, Barthes and Camus and immediately afterwards striking you with a Woody Allen joke, punctuating her tales with anecdotes from her days as a liaison with NASA in Washington for the European Space Agency, then calling for better treatment for mathematics in schools and moving on to an etymological explanation of the word desire (“the condition in which one is far from the stars”), finally digressing into neuroscience (Antonio Damasio contributed to the exhibition upon her invitation).

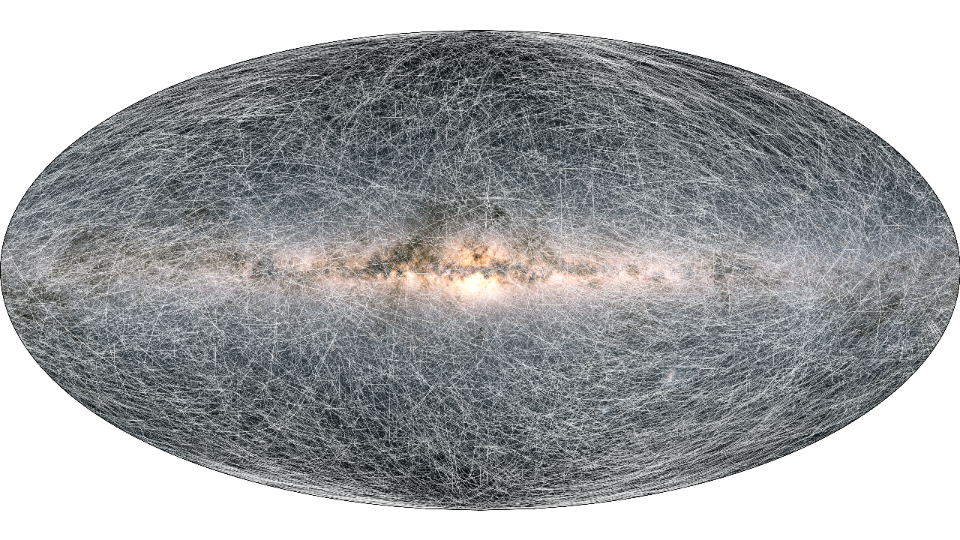

There are two keywords in our conversation. One is emotion, the other is mathematics, and she emphasises several times the need to study it. With serene sophistication, with her persuasive, almost hypnotic cadence, she describes interstellar nightmare scenarios, galaxies eating each other, dying suns, not to mention the predicted end of the world as we know it aka the dear old solar system, wiped out by a colossal collision with Andromeda, which until yesterday I identified at best with the gender-fluid knight of the zodiac – (always on the subject of diversity) –, and not with some sort of Thanos of astrophysics who wipes out entire ecosystems (ours!) with a snap of his fingers.

Outside the comfort zone

The unknown certainly does not sound like a comfortable place, but Ersilia Vaudo decided to live outside her comfort zone a long time ago, when she chose physics. “You have to abandon certainty if you want to understand something,” she says. That discipline is certainly not the realm of common sense, and phenomena such as gravitational time dilation, or the loss of the third dimension of superfluid helium in quantum mechanics demonstrate this well. But when narrated by her, they sound like poetry. For Vaudo, physics is a story to be shared, a “moment of excitement and wonder”, and this is exactly what she brought to the Triennale, to the temple of human endeavour – the grand narrative of what humans do not need at all.

In the exhibition curated by ESA’s Chief Diversity Officer, diversity could not but be a crucial element. “I didn’t want to make it polarising, but rather enriching,” she explains. Here, artists, musicians and art historians run side by side with architecture and science, “a condition for imagining new things and at the same time an exciting occasion to see six points of view become seven, eight or nine”. Because the way we look at the unknown is the heart of the matter, Vaudo observes. And to escape from the ease of turning the unknown into a stereotype, but also to prevent “her” exhibition from being perceived as a scientific patronizing device, Vaudo relies precisely on multiplicity, on the “idea that something new happens when you put several points of view together”. Diversity thus becomes the privileged observation point on that 95% of the universe that we do not know.

Extraterrestrial architecture

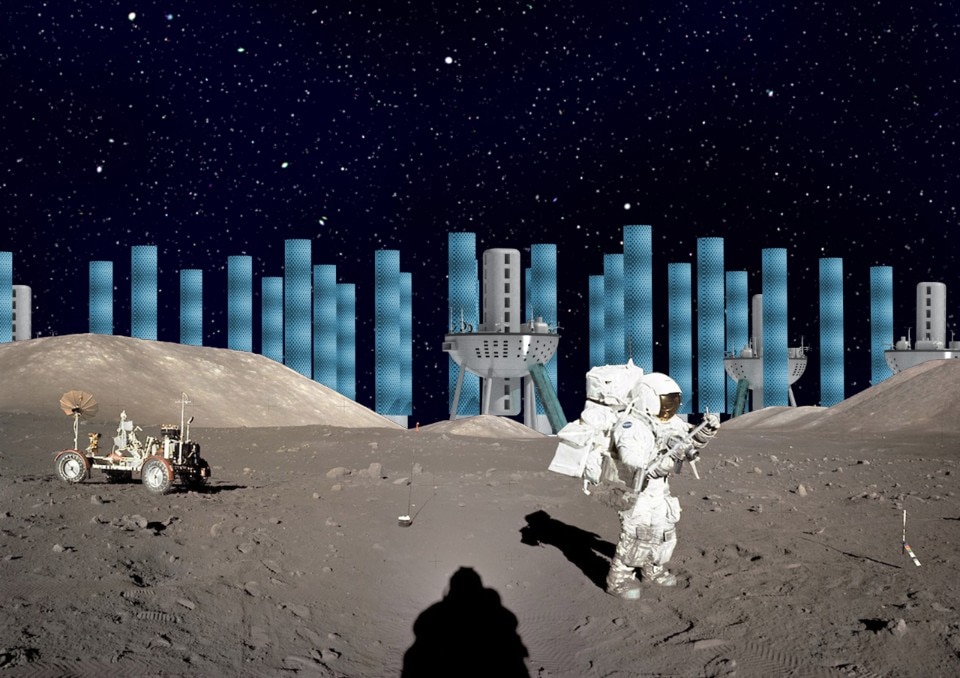

The layout of “Unknown unknowns”, designed by Joseph Grima’s Space Caviar, is shaped like a semicircular orbit, with a ground grid representing the curve of space-time. To make it, they used organic waste material from rice processing which was “fed” to Wasp’s 3D printers. This was a sustainable choice, but also a symbolic one, as it traces the probable approach of our future building far away from the earth, “something that is already happening,” as Vaudo explains, mentioning ESA’s experiments on the use of lunar regolith – which covers almost the entire surface of the satellite – as a building material.

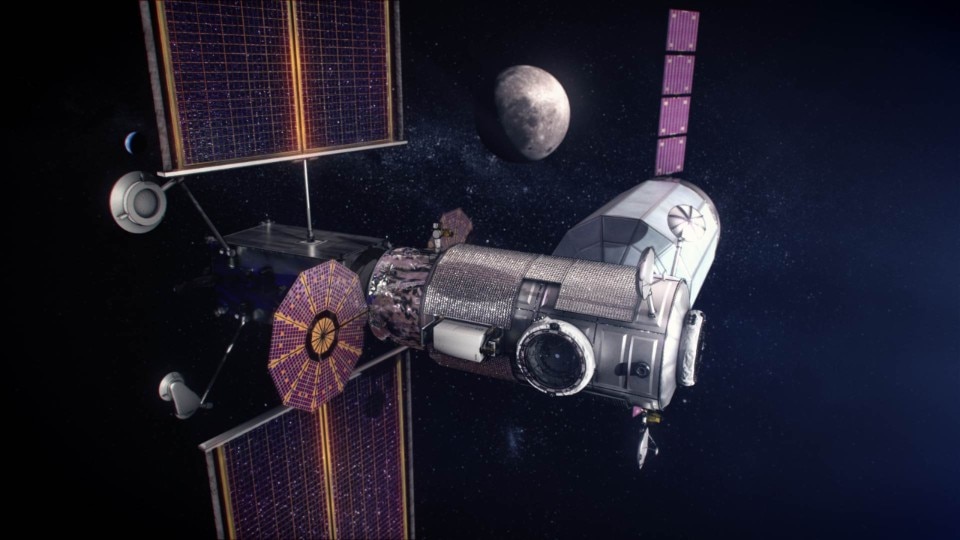

“We are going there to stay,” says Vaudo, when talking about architecture outside our planet, which will have to face unprecedented challenges – first of all, the different gravity on the Moon and Mars, which for those working in the design field overturns almost all scenarios. Part of the exhibition is dedicated to this theme. Colin Koop from SOM designed a lunar village for ESA and has prepared a decalogue of rules for the international exhibition for those who would like to study extraterrestrial architecture. After all, Nasa’s Lunar Gateway is (almost) our present, as it will be built over this decade, and man stepping foot on Mars by 2040 is the future.

According to Vaudo, 3D printing will change the way we design everything. “Today, we tend to associate it with a way to make Dolce and Gabbana sunglasses at home,” she says ironically. “In reality, 3D printing is a completely different design process”. This method of constructing objects proceeds layer by layer, “as nature does”, emphasises the astrophysicist, who shows me on her phone some pictures of a strange tool, with essential, almost brutalist lines, that they made at ESA. It is a screwdriver, but it was rethought through an algorithm and redesigned around the torsion zones and not according to what we normally think a screwdriver should look like.

But that is not all: 3D printing will also be used to “fix” the first humans to visit Mars. Vaudo tells us about some experiments to reconstruct entire portions of the skin of the first explorers, which could burn themselves due to the planet’s climatic conditions. “Even Elon Musk said that ‘it will not be fun’”. It will not be fun at all.

![Mars Desert Research Station #11 [MDRS], Mars Society, San Rafael Swell, Utah, U.S.A., 2008 © Vincent Fournier / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_500,h_500,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-theravestijngallery/usr/images/press/main_image/items/62/62aabb4bbcc24d2386e02636a9a73eeb/11110e32ba174ef28858d3d59fa9e4e4j.jpeg)