There’s more than meets the eye in the centuries-old farmhouse that the Dutch artist Ruth van Beek calls her home and studio. Located in the idyllic small town of Koog aan de Zaan, her forest-green house is picturesque and holds a mesmerizing archive and workspace. Last summer, I rang the brass buzzer to meet with Van Beek, who has lived and worked here for more than twenty years. The structure offers an appropriate backdrop for Van Beek’s artwork, a distinct exploration of photography and collage that uses archival images, bizarre folds, and pastel-colored shapes to often obstruct what lies in view.

Van Beek was born and raised in Zaanstad, a municipality just northwest of Amsterdam along the slumbering Zaan River. She moved to Amsterdam in the 1990s to study photography at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, where she discovered both her appetite for playing with found images and the power of context. “I am very interested in the malleability of photography,” Van Beek explains. “By taking images out of their own context and placing them in an entirely new one, I make them part of my world. That’s a fascinating game.”

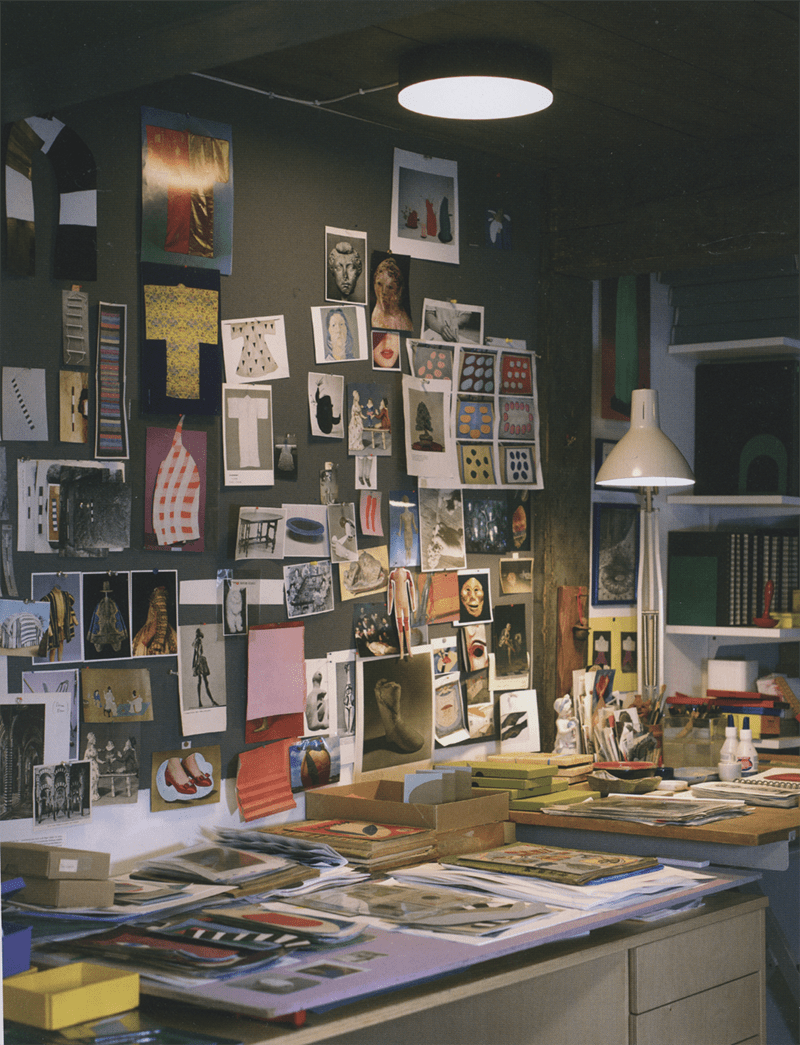

Walking into Van Beek’s creative space, the first thing that strikes you is the wild abundance of visual stimuli. A bulletin board filled with curious pictures from vintage magazines; bookshelves brimming with guides to the art of homemaking and floral arrangements, along with stacks of her own publications; walls with a larger-than-life print of a doll’s miniature socks and oddly shaped watercolored cutouts; and much more.

“I began using found photographs from abandoned family albums during my studies. I found them bizarre. They struck me as nostalgic, but also tragic, to find someone’s precious life discarded at a flea market,” Van Beek says. The voyeurism was the first thrill, but she describes needing to surpass the sacred—to take control, to make art. “I had to take a knife to it, quite aggressively. I started cutting and folding the photographs. What it emphasized was that it was about the object.”

Van Beek describes the first act of her process: Deconstruction and transformation. Removing the object from the frame. A subtle spin of the absurd. A practice of manipulating what it is that we think we can see. She has devised an elaborate archival system to organize her source material. Stacks of boxes of still-life photographs, sliced from glossy encyclopedias and magazines, are tied together, with labels ranging from “walking and standing” to “house plants” to “artifacts.”

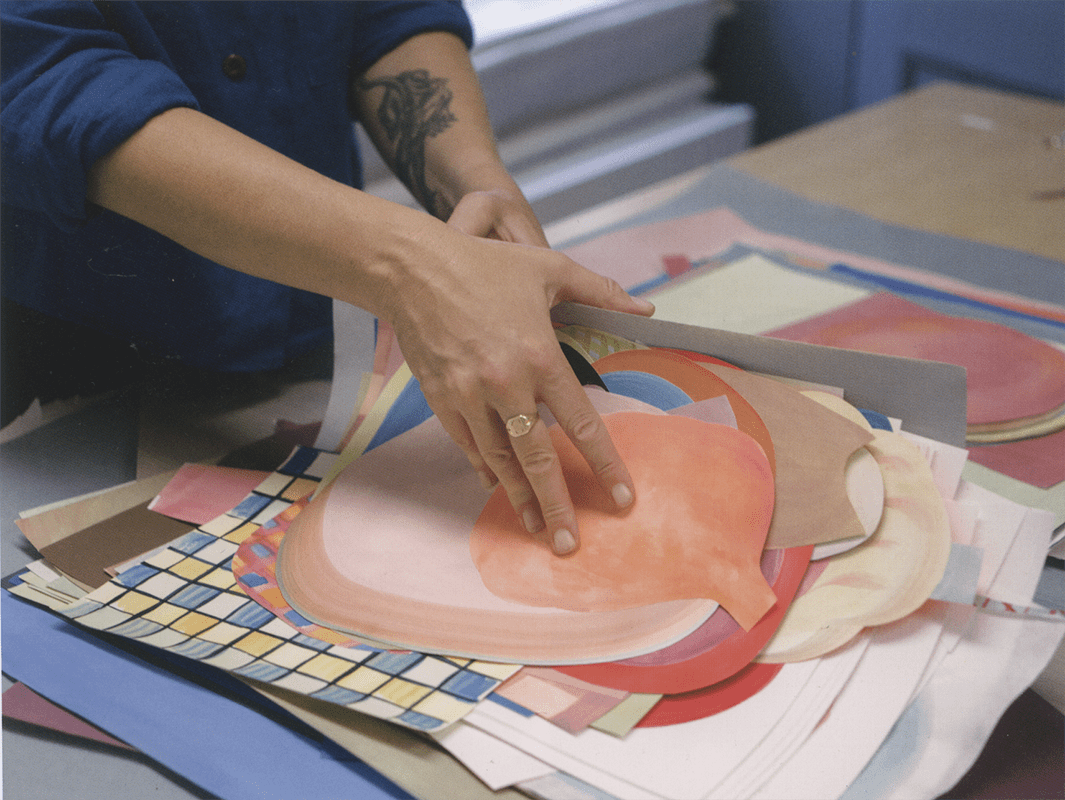

Her worktable and walls are also adorned with objects of her own creation: organic shapes cut from paper and painted with watercolors, ready to cloak and distort the photographs at hand. “My work has to do with covering up. About what is created by obscuring the image to show you something new. Just like an apparition or a ghost, you throw a sheet over it to reveal its shape.” Her constructions may expose only the sliver of a shadow, the tip of a toe, a suggestion of more. They invite you to see what is brewing under the surface.

The pairing of photographs and collages comes together in her long-standing tradition of bookmaking. One publication, How to Do the Flowers (2018), is made up of detached hands in action; it shows us that “anything is possible if you place images next to each other. It breaks everything open,” as the artist explains. Bringing together hundreds of visual sequences from her picture archive, and driven by a hidden narrative and the wry command of the title, the book “is also a self-portrait of the process of creating. A way to share my instructions for absurdism.”

Ruth van Beek and her studio, Koog aan de Zaan, the Netherlands, July 2024. All photographs by Samira Kafala for Aperture.

The soft tension between the chaos and the charm in her studio sets the perfect stage for Van Beek’s playful yet complex image making. “My work is neither sweet nor nostalgic,” she says. “My space is not an ode to romantic relics either. If you look past the first layer of attractiveness, with sweet colors and soft tones, there’s an uncanny feeling lurking behind it.”

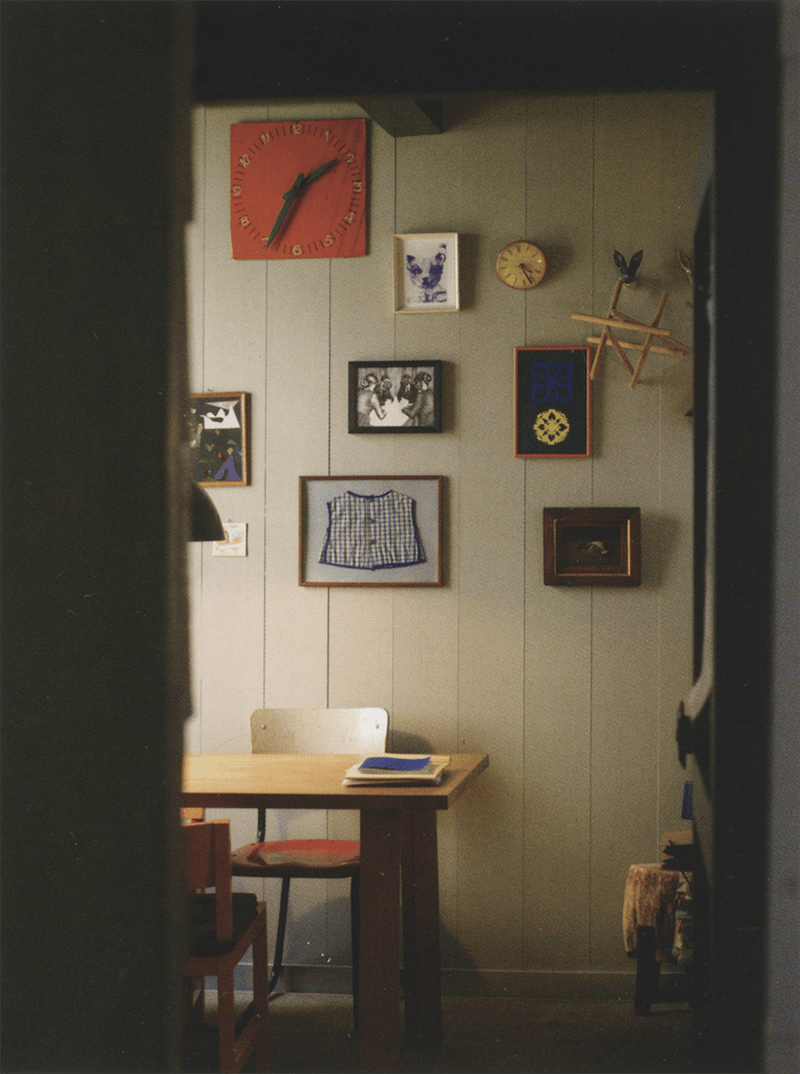

Van Beek recounts the past lives of the studio walls, from garden house to bygone clockmaker’s workshop. But stepping into the studio today gives you the funny feeling of entering the artist’s mind—a personal maze of interconnected images and obsessions. “It’s kind of an extended brain,” she muses. “I like everything within hand’s reach, so I can encounter things again and again. There’s a constant flow of visual connections and intuitive gathering.” As we circle the space in search of the next images to flip through, Van Beek smiles knowingly. “It’s good for me to escape the studio sometimes, not get in too deep,” she says. “It’s like a psychosis that you bring on yourself. It needs to be in small doses.”

—Roxy Merrell is a writer and editor based in Amsterdam.