The subtitle of Patrick Waterhouse’s latest work, Restricted Images, is Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia – and the word ‘with’ is notable. Over repeated trips, the 37-year-old Briton began to collaborate with, photograph and collect the work of Warlpiri artists, basing himself at the Warlukurlangu Artists art centre in the Northern Territory, five hours’ drive from Alice Springs.

“I wanted to create a situation where the people I was working with had an encounter again, a chance to flip the power dynamic,” he tells me over coffee at his new studio in east London. He is surrounded by prints from the series, neatly packaged and ready to travel with him two days later to Australia for the next chapter of a project that started in 2011 when, through his editorship of the iconic Colors magazine, he first visited the art centre. “I wanted to give the people in this community agency over their own representations,” he says.

Installation view of Restricted Images at The Ravestijn Gallery

To understand the nuances of the work, it’s worth attempting to decipher the troubled relationship of the Warlpiri with the medium of photography. Scattered across their traditional lands north and west of Alice Springs (a landmass roughly equivalent to that of Italy), there are between 5000 and 6000 Warlpiri, living mostly in a few towns and settlements. These indigenous Australians first came to the attention of a European audience with the publication in 1899 of a book, The Native Tribes of Central Australia. Its authors, a telegraph-station master called Francis J Gillen and ethnologist Walter Baldwin Spencer, wrote in depth, and for the first time, about the customs and traditions of the Aboriginal groups living near Alice Springs.

“Baldwin Spencer and Gillen were the founding fathers of the notion of fieldwork in anthropology, and their use of photography was a key aspect of their practice,” Waterhouse says. “They influenced anthropology right across the world. But their legacy is a complicated issue.”

The book’s texts were illustrated with 119 photographs, many of which captured the rituals and ceremonies of Australia’s indigenous people. By publishing the photographs, Waterhouse acknowledges, Gillen and Baldwin Spencer infringed upon Aboriginal cultural beliefs, in part by publishing photographs of sacred sites and burial grounds. “In many ways, they were the liberals of their time,” Waterhouse says. “They reached outside of their culture and actually looked to understand people. But, looking back now, their work is deeply problematic. It opens up a whole series of issues around the power dynamic in photography – the person taking the photograph, and the person in the lens.”

As such, Waterhouse is using this intersection between anthropology, ethnography and photography as his starting point, and rethinking the humanistic values they embody in a 21st century context. By returning to the same sites, and photographing the same communities, Restricted Images can be viewed as a rejoinder to the birth of anthropological photography that has not been fully challenged before. “While the subject, quality and quantity of the images set a new standard for anthropological photography, the authors were largely oblivious to the impact they would have on the lives of the Aboriginals,” Waterhouse writes in an opening statement about previous works.

“The pictures revealed the gap in knowledge between the authors, whose goal was showing the exotic natives ‘in their natural state’, and the subjects, who were completely unaware of the new medium and how it could invade their privacy and reveal their secrets to a wider audience.”

These days, there’s a great deal more sensitivity to Aboriginal culture, and there’s now an understanding of how the dissemination of photography can impinge on their belief systems, proving destructive in ways that would have been unforeseen by the Victorian ethnographic pioneers. Today, photography within Aboriginal communities is limited. In addition, photographic and cultural institutions across Australia and Europe have restricted access to archives of colonial-era anthropological artefacts. In many cases, only the descendants of those depicted can decide who is allowed to access them. “There is now much institutional uncertainty about how to approach the question of representation,” Waterhouse says.

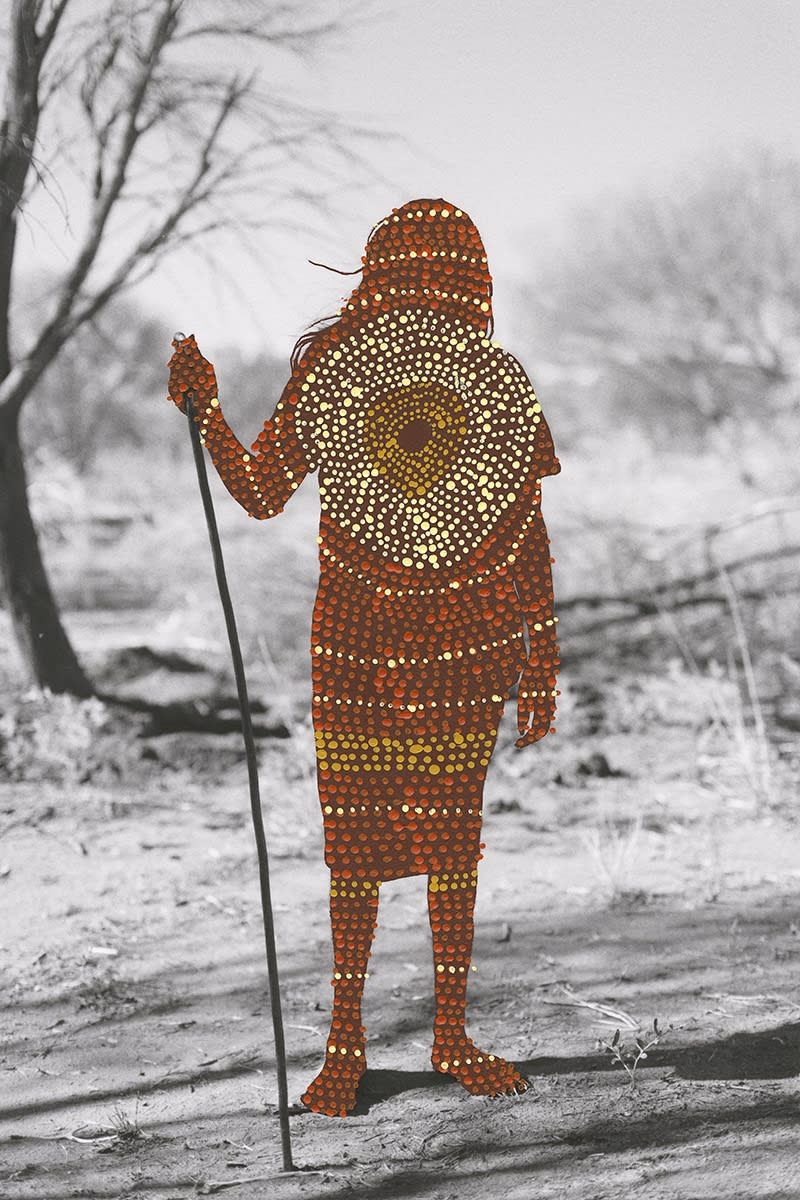

Still Making Camp. Restricted with Joy Nangala Brown, 2014 - 2018 © Patrick Waterhouse / courtesy The Ravestijn Gallery

Still Making Camp. Restricted with Joy Nangala Brown, 2014 - 2018 © Patrick Waterhouse / courtesy The Ravestijn GalleryAs the Restricted Images project developed, and as a way of navigating this ethical and practical issue, Waterhouse started to return to his new- found collaborators in Australia with prints of photographs he had taken on previous trips. He did so, he says, to allow his collaborators to “restrict and amend my photographs through the process of painting”. He invited the Warlpiri to add to the surfaces of the images using the traditional technique of dot painting. He was “thus enacting their own restrictions upon them” as a way to “symbolically return to these communities agency over their own images”.

Waterhouse sees in these images a wider inquisition, a multivalency that comments not just on the Aboriginal experience, but also “how we tell the stories of the history of colonisation and the forming of a nation”. He points out that the history of the British Empire is not widely taught in British schools, and is often viewed by many UK citizens, and indeed members of the Commonwealth, as a polarised, binary debate between jingoistic pride and a critique of imperialism.

“We don’t have a conversation around it, but the history of the Empire has formed so much of our country’s current situations,” he says.

The series, evidently, has been long, involved and intense. Waterhouse’s first trip closely coincided with his appointment as editor-in-chief of Colors in Treviso, and came alongside his decision to create a new editorial direction for the magazine with the introduction of a series titled The Survival Guides. It also came off the back of his own emergence as an artist, after he was awarded the Discovery Award at Les Rencontres d’Arles in 2011 alongside South African photographer Mikhael Subotzky. Their joint work, Ponte City, depicting a 54-floor apartment block in Johannesburg built in 1976 for a white elite under apartheid rule, and now a symbol of urban decay, was in the process of becoming a photobook published by Steidl, and would go on to win the Deutsche Börse prize in 2015.

There’s a lineage between Colors’ unique position in the publishing world and Waterhouse’s personal practice, for the ethos he pursued with The Survival Guides seems to be something of a blueprint for his approach to Restricted Images. Over Waterhouse’s shoulder, lined up carefully on a plywood bookshelf, are the many issues of Colors that he edited, each following a particular theme, from Happiness to Apocalypse, Transport to News. Every issue is thick, vivid and carefully bound, resembling something you’d find on the shelves of a bookshop rather than on a typical magazine stand.

Colors was founded in 1991 as “a magazine about the rest of the world” by photographer and serial provocateur Oliviero Toscani, best known for his brilliant-but-controversial campaigns for Benetton, and was initially edited by legendary art director Tibor Kalman, who implanted the idea that photography, typography and design were essential and complementary to the magazine’s journalism – as integral as its writing, reproduced in seven languages. And it was Benetton that sponsored the magazine, granting Colors a degree of independence rarely seen in commercial partnerships, later establishing Fabrica, its communication research centre in Treviso, nurturing young talent from the fields of photography, design, video, music and more, from which Colors was produced.

“Both Colors and Fabrica understood they would be more effective through creating work and communication which expressed values,” said Waterhouse in an interview with It’s Nice That, “something companies often struggle to understand has an intangible worth – as opposed to just promoting products”.

Colors made a name for itself as a proponent of slow journalism. Each quarterly issue came from months of painstaking research, and combined long-form inquiry with graphic design and original photography used in ways rarely seen elsewhere. After the initial trip to the Northern Territory in 2011, Waterhouse applied the approach he’d developed at Colors to the issue of representing Australia’s Aboriginal peoples. He set about developing a body of archival documents about Aboriginal culture from The Native Tribes of Central Australia onwards, finding revisionist maps, school books “that told the story of plucky Englishmen discovering things”, scientific manuals and old lithograph portraits – any sort of ephemera that might shed light on the “competing historical narratives” of Australia.

“I went to museums and private collections across Australia, England and parts of Europe and acquired real bits of the historical record of the European encounter with Australia, and the way in which that story was told.”

Once compiled, he took the archive to the Northern Territory, setting up at the Warlukurlangu Artists art centre. “Initially, the project was about going over and talking about the archive,” Waterhouse says.

“They were apprehensive, but they were willing to let me come and try.” The dialogue Waterhouse had over this time led him to reflect that “while I was going through all this critical thinking about the past, I wasn’t applying it to the pictures I was taking at the time."

Restricted Images has now been turned into a photobook by London-based Bruno Ceschel of SPBH Editions, another Colors alumnus. It looks set to make a splash, no doubt making its presence felt at festivals and book awards across Europe and North America. But, as Waterhouse is preparing to fly out to Australia for the book’s premiere at the Desert Mob Symposium in September, and an exhibition at Desart in Alice Springs, it is there that his real audience waits.