Often illusionary, occasionally subversive, and invariably crafted from a broad toolbox of materials and techniques, Theis Wendt’s works reflect his preoccupation with age-old questions of the human relationship to authenticity.

In conversation with George H. King, Wendt traces the origins of his artistic interests, pointing to a crucial technological shift that steered his practice forward.

-

-

GK: First things first, I’d love to get a sense of where your relationship with the arts, or with making, began? Were you a creative child?

TW: Not really, I was just a ‘normal’ kid, growing up in a typical nuclear family in a small village in the Danish countryside, hanging out in the sports hall, playing handball, stealing apples from the neighbour - just being a kid really!

GK: Was someone else in your family the creative force, then?

TW: My mum painted every now and again. She’s definitely the creative one when it comes to my parents, but it wasn’t a huge influence; it wasn’t my entrance into being creative, anyway. That came a little later.

As a teenager, I’d definitely gotten bored of this little village – and with studying – so I had an urge to get out and experience the world a bit more. I ended up at a business school with some pretty cool people, most of whom dropped out within the first few months! One classmate introduced me to the leftist political scene in Copenhagen, around the same time that graffiti had first caught my attention.

-

"Humans have colonised this whole planet – recorded it, ploughed it, polluted it – and our traces will most likely be here long after we’re gone." - Theis Wendt

-

GK: Was this a bit of lightbulb moment for you?

TW: Yeah, for sure. I guess my creativity was maybe born out of a pressure, of not really fitting in to what was expected of me, maybe? Quite normal stuff I think. But this whole experience of going into the city, interacting with it, painting on it, using it as a kind of playground, basically – that really made sense. So I quit handball and started to paint graffiti, almost from one day to the next. It was a total U-turn!

GK: So, having found your creative impulse, you later wound up at art school. What did that journey look like; from painting graffiti to the Academy?

TW: Yeah, well I think being creative – painting, drawing, sketching – just opened my mind a lot, and my view of the world. Then, when I was 16 or 17, we had something called the Free Youth Education in Denmark. It was a kind of experiment by a social democratic government where you could structure your own education – you could go to whatever kind of art school, learn surfing, anything. It was quite incredible! And of course they shut that down after a few years, but I was lucky enough to jump between different art schools – with a semester here and there. So after three years of that, I ended up at an art school in Barcelona called Metàfora. That’s really where I got a foundation in art history. And from there, I applied to the Academy back in Copenhagen and I was accepted, which was lucky!

-

GK: Nowadays, many of your works – which are very diverse in form – seem to play with ideas of reality, authenticity and representation. But looking back on the kind of stuff you were producing at the Academy, could you already see these interests coming to the fore?

TW: Yeah, funnily enough, the work I applied to the Academy with is somehow still related to the work I’m making today, though I didn’t have a clue! I couldn’t fit it into any kind of framework back then. It was a street project where I found three different objects – well 2 objects, and a text that someone had written on a wall with a spray can. I photographed each of the them and then glued my image beside the original, as well as documenting the process. So I guess this was a starting point for my interest in an original, its relationship to a representation of an original, and this process of creating the representation.

At the Academy, I guess I made a lot of work that was kind of subversive in a way. There were projects that involved fake signatures and fake letters, this kind of thing. Back then there was a small newspaper distributed in the subway in Copenhagen, and together with a friend – which was also just a bit of fun – we made our own ‘fake’ version, inventing our own stories but using their aesthetic and graphic design, then distributing them in the subway. So it was in that sort of thread of playing with authority and authenticity.

-

But in the meantime, it wasn’t as if I’d suddenly gone conceptual or whatever, though. I was still doing everything! Painting, group work, sculpture, just being as confused as possible and having fun.

-

-

"Of course, an artwork is nothing when a real crisis – the real tsunami – arrives. We don’t need artists then of course, we need engineers, aid workers! But us creatives need to communicate in as many different areas and languages as we can." - Theis Wendt

-

GK: How do you feel that time period compares with today?

TW: It’s almost as if the presence of the technology is normal now, it’s accepted. Whereas at that time there was this consciousness that these changes were going to have a huge impact on how we would connect with and perceive one another. That was sort of my point back then, that trying to perceive the physical world and the digital world as two different things was going to become more difficult; they were already entangled to the point where even talking about the distinction between an object and an image of an object, for example, was not really easy.

GK: So in what way does your work respond to this shift, these questions?

TW: I think it’s really important to question that entanglement, to examine the borders of what’s what. That’s very much what I do; I want to find an aesthetic, or materialise something that’s invisible to us in a way. Digital representations of being are clearly changing our perception of presence, and nature is also increasingly challenged by human interaction, So I think we need an aesthetic to be able to grasp these changes. Ultimately, I’m trying to question the consensus about authenticity; about the ‘real’ world.

-

GK: As well as this tension between reality and representation, you’ve also just touched upon your interest in nature, and how we understand it. Could you expand on that a bit?

TW: I’d say the notion of the Anthropocene has been a huge influence for me. Given my interest in authenticity, it’s hard to avoid the concept, because nature’s always been a recurring point of reference for identifying what’s authentic or real. It’s definitely become a buzzword in recent years, but for me it’s still a helpful tool for rethinking our relationship with nature.

-

"Humans have colonised this whole planet – recorded it, ploughed it, polluted it – and our traces will most likely be here long after we’re gone."

-

Surely we can’t still think of ourselves as little figures in a Romantic era Caspar David Friedrich painting, you know? That old background/foreground distinction has collapsed, the horizon doesn’t represent the same symbolic interpretations of the beyond anymore, and we know what’s out there now – what’s on the other side of the landscape. But somehow it’s hard for us to avoid that Romanticist notion of the sublime, even though we’re so intertwined with the sublime at this point.So if nature doesn’t mean the same thing anymore – if we can’t define it – we need new ways to talk about it. A new aesthetic; new images. In my work, that means tapping into this Romanticist notion of beauty and sublimity but through synthetic or virtual mechanisms. It’s about trying to conjure that primordial sensation of nature but within the frame of something artificial or constructed. So a work might look like a painting of a landscape, but on closer inspection, it’s actually a resin cast. Or it’s about evoking that sensation of light flickering through the trees in a forest, but doing so via a 3D animation projected onto the floor of an old coal factory. Does that make sense?GK: It does! And as you’ve said, the Anthropocene concept is everywhere nowadays. But is it possible, or is it a naive expectation, that the arts can contribute something meaningful to conversations such as these?TW: Even though I’m questioning these representations of nature from the Romantic era, I’d call myself a romanticist when it comes to believing in the potential of art and the things it can evoke. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be working with it. Many producers of culture – designers and architects as well as artists – belong to a movement in this regard, and I think culture in a broader sense has been really influential in awakening many people to what’s going on in the biosphere.

-

"Of course, an artwork is nothing when a real crisis – the real tsunami – arrives. We don’t need artists then of course, we need engineers, aid workers! But us creatives need to communicate in as many different areas and languages as we can."

-

The impact might be limited or hard to measure. But its potential is also unlimited, in the sense thatit is creative, so I think we can front-run quite a lot of conversations from a free space like the arts.

-

GK: Is there anyone, or anything in particular, that inspires you in your work?

TW:The things that inspire me are really diverse, but the names that come to mind aren’t necessarily reflected in what I’m producing. The Dutch video-installation artist Aernout Mik, for instance, was very important for me at a point. I love the paintings of Philip Guston, and I think the Light and Space movement was probably also a huge inspiration.

I don’t know if I’m directly inspired by other artists, though. I read philosophy – not that I’m a hardcore academia dude – and sometimes I don’t get all the things I read. But thinkers like Timothy Morton or Franco Berardi Bifo have inspired me a lot. Bifo’s book After the Future was quite an eye-opener, as was Morton’s Hyperobjects and Ecology without Nature. Reading is always a nice space for thinking, interpreting, and misinterpreting!

-

-

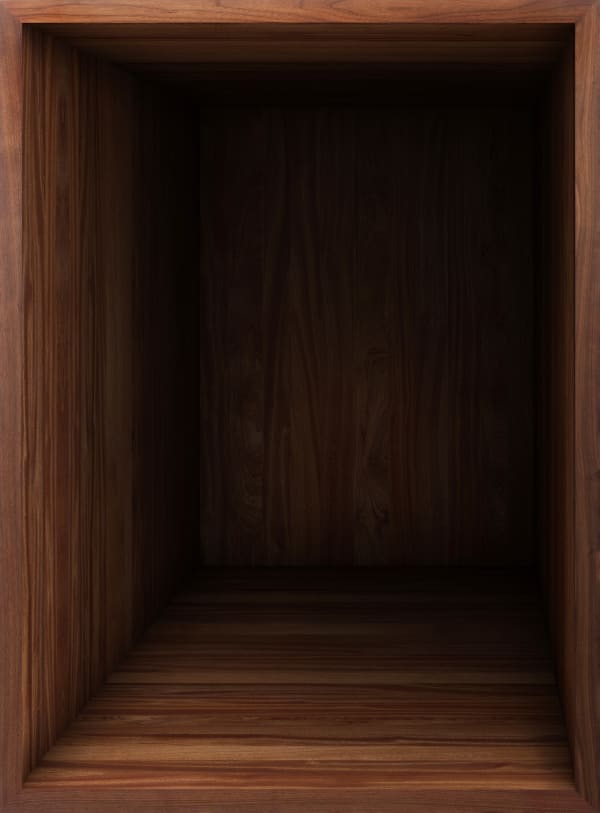

GK: For sure! Now, we’ve spoken about a lot of different stuff: about nature, but also about authenticity, Romanticism, and this kind of illusionary feeling that your works create. Maybe it’s helpful to zoom in on some particular works, like your wood frame pieces for instance?TW:Yeah, so those works take the form of extruded empty frames – a combination of the frame itself, photographs of a texture that’s similar to the frame, and a digital extrusion. It’s this fusion of an organic and a digital materiality. For the viewer, the extrusions generate the illusion of holes in the space, so people normally move around a lot in front of them, investigating different angles and perspectives.These particular pieces attempt to deal with the paradox of trying not to create an image, but ultimately still doing so. This in turn reflects another paradox of contemporary life: that it’s hard to resist what we’re immersed in, be it digital screens or technology or capitalism. How can we avoid, critique or abstain from something that’s constantly going on around us, that infiltrates so much of our lives? In many ways, the work is about that tension.

-

-

GK: And your pieces with the blinds? Into the Night or Dwell, for instance?TW: Those works were also informed by an interest in painting and frames from an art historical perspective; of a painting being a window into something. And I think they show in a very direct way a kind of double-sided window, tapping into a broader idea about inside vs outside, or of the distinction between foreground and background kind of collapsing.In a material sense, they’re real Venetian blinds which have been submerged in pools of resin. The blind sits just underneath the surface, but it also protrudes in certain places. I like to look at it as a sort of double view. It’s a window that you’re looking into – or out of – at the same time. It’s also not really a blind anymore, it’s like an object that is becoming an image, or an image that’s partly an object. In that sense it’s about an image losing its referent in a way, which reflects how the digitalisation of the world has seen images become more important than ‘real’ experiences for some people.

GK: What do you hope your work might be able to do for those looking at it? Do you have any particular aspirations?

TW: My work tries to create a space for reflection on our changing world, and I’d like the viewer’s first impression to be a feeling of doubt about what they’re looking at. I think that’s a good starting point for looking at anything at all.

-

For more information on available edtions and prices, please contact the gallery via phone at: +31 (0)20-5306005 or via email at info@theravestijngallery.com

-

ART FAIRS

-

PAN 2022

Patrick Waterhouse (UK), Scheltens & Abbenes (NL), Theis Wendt (DK), Cortis & Sonderegger (CH), Matt Lipps (US) 14 - 21 November 2022Private opening: 19 November 2022 / 12:00 - 20:00 Public days: 20 - 27 November 2022 / 11:00 - 18:00 At PAN Amsterdam 2022, The Ravestijn Gallery presents a selection... -

Paris Photo 2022

Group presentation Inez & Vinoodh, KYoung, Eva Stenram, Theis Wendt & Tereza Zelenkova 8 - 13 November 2022During Paris Photo 2022 The Ravestijn Gallery presents 5 artists in the online viewing room: Inez & Vinoodh (NL/US), KYoung (UK), Eva Stenram (SE), Theis Wendt (DK), and Tereza Zelenkova... -

UNSEEN 2022

Katie Burnett, Asger Carlsen, Pacifico Silano & Theis Wendt 15 - 18 September 2022Opening: Thursday 15 September, by invitation only Fair: Friday 16 September 11.00 - 21.00 Saturday 17 September 11.00 - 19.00 Sunday 18 September 11.00 - 19:00 The Ravestijn Gallery is... -

Art Rotterdam 2022

Group presentation with Inez & Vinoodh, Nico Krijno, Michel Lamoller, Scheltens & Abbenes, and Theis Wendt 19 - 22 May 2022The Ravestijn Gallery is proud to present Inez & Vinoodh (NL/US), Nico Krijno (ZA), Theis Wendt (DK), Scheltens & Abbenes (NL) and Michel Lamoller (DE) at Art Rotterdam 2022.

-

-

Press

-

Art Rotterdam: The Ravestijn Gallery Amsterdam

May 24, 2022The well-known Amsterdam gallery The Ravestijn Gallery presents five projects with the well-known fashion photographers Inez & Vinoodh van Lamsweerde Matadin, as well as four projects balancing between plastic arts... -

'Negative Meadow' by Theis Wendt at Kunsthal Nord, Aalborg

April 11, 2019The virtual world is an essential theme in the exhibition Negative Meadow, which encourages the viewer to explore and sense the intertwinement of the virtual and the present reality. The... -

Theis Wendt at CINNNAMON

July 16, 2017Nature is not what it used to be. It is changing, transforming and mutating, way beyond our current knowledge and wildest imagination. This is not something new. The billions of...

-