-

Words by George King

Illusions abound in the distorted visual world of Koen Hauser (b. 1972, NL), whose richly-rendered photographic projects are united by a central preoccupation with reality – namely, the impossibility of representing and perceiving it. His latest project, Michelangelo Iconoclastia, takes a ubiquitous art historical catalogue as its starting point, spinning its contents into surprising new forms with a helping hand from AI. Here, Hauser plots the points of a career in image-making, reflecting on the changing tools that have shaped his creations to date.

-

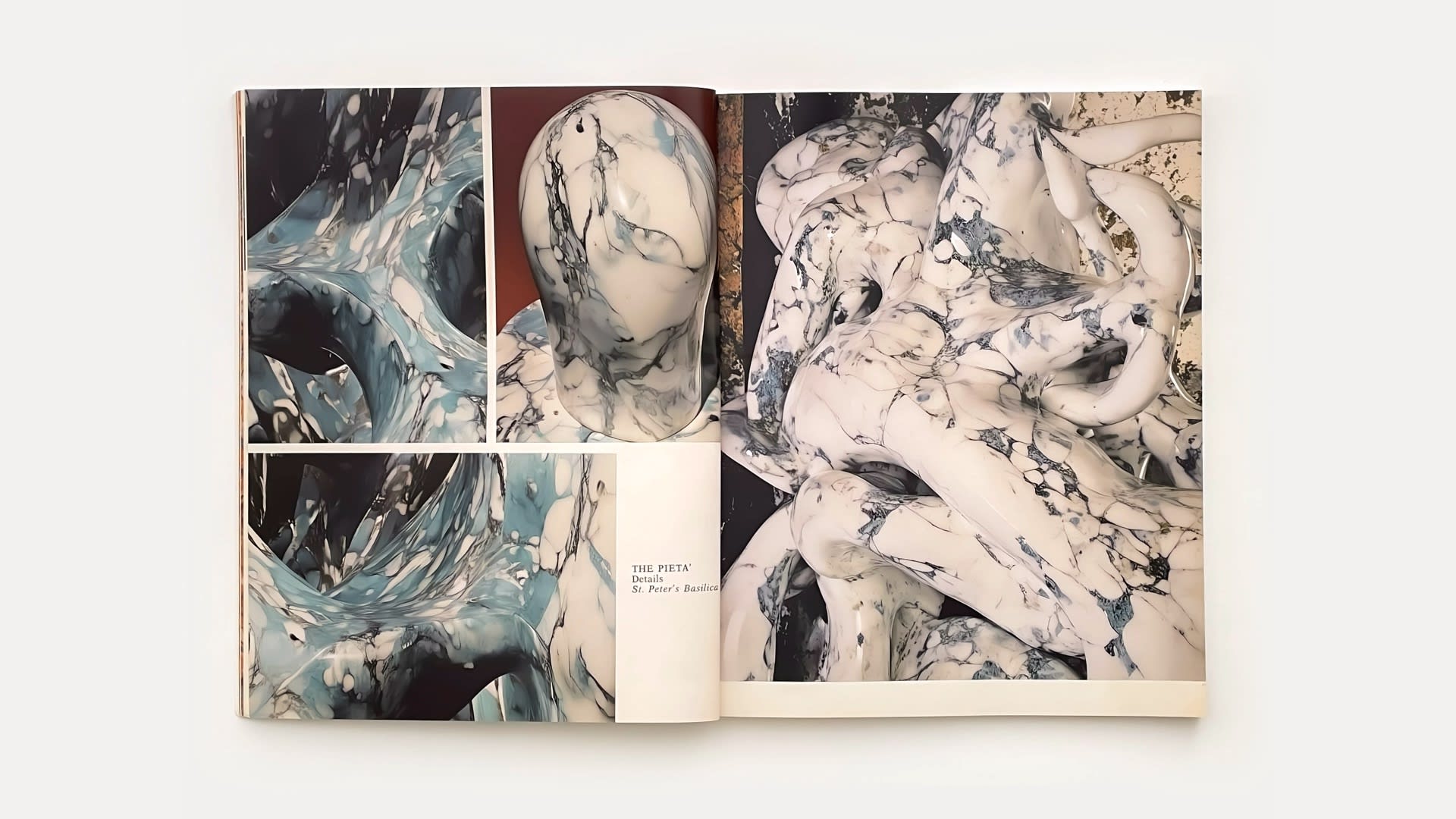

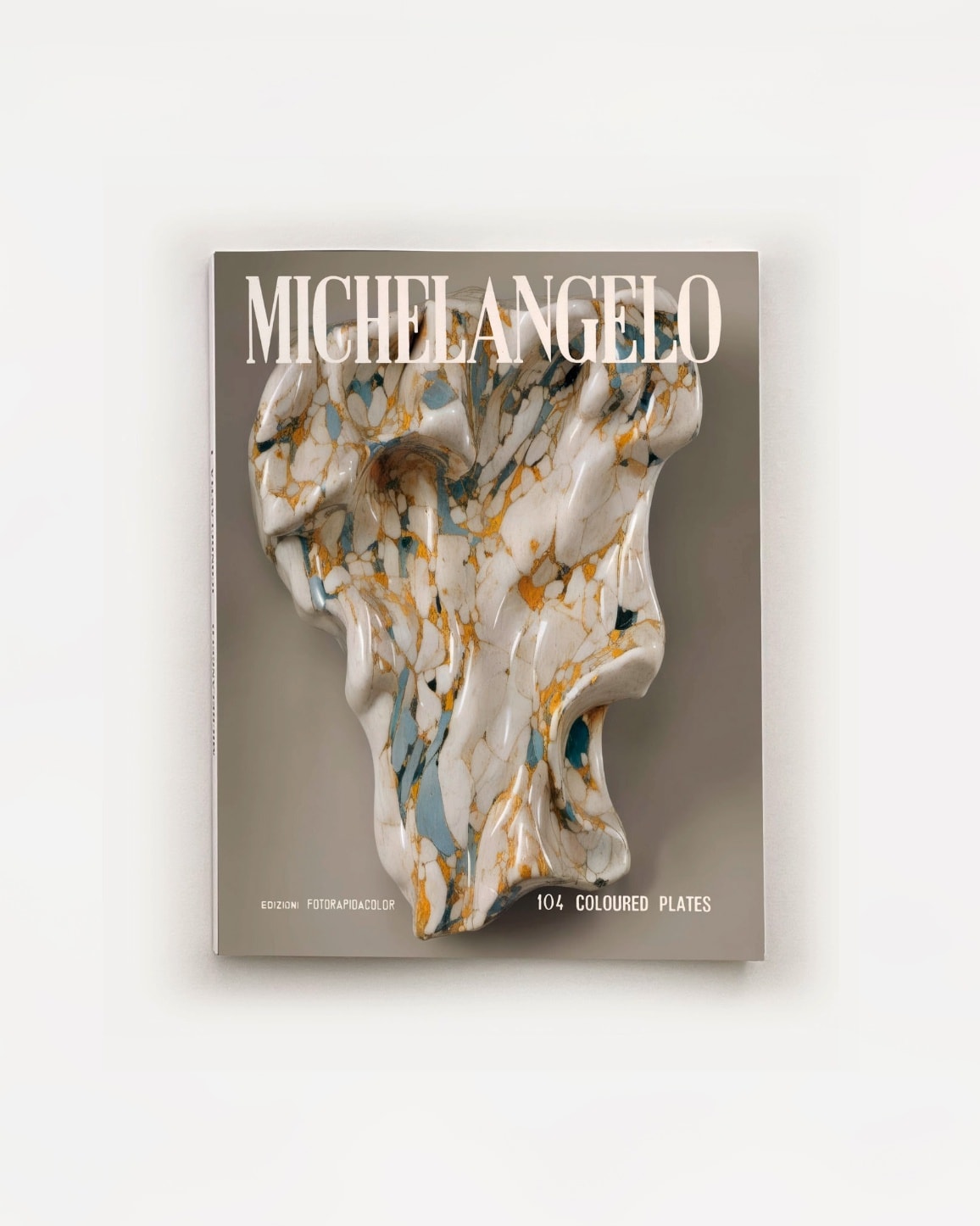

Pages from a variation of a Michelangelo Iconoclastia Artist Book (marble objects), 2024

-

-

-

-

George King (GK): Where do you think your love of images first came from?

Koen Hauser (KH): I recently gave a lecture for a class of medical students – on the connections between medicine and art – and I started by talking about this medical encyclopaedia my parents had at home when I was young. I was fascinated by it, I was really charmed by its visual language! Other than that, I didn’t have much interaction with the arts. I came from a working class family, and the only museums I ever saw from the inside were natural history museums.

Later, I happened to be able to go to university – which no one in my family had done. I studied Psychology, which in the end was super fascinating. I was on a path through academia, to do a PhD, but I always hated the very theoretical parts of that world. Looking back, I also realize I wasn’t really challenged to think for myself. So I started thinking again about photography, which I’d first become interested in at high school. I’d learnt how to print, and I really liked doing analogue stuff. Then came Photoshop 3.0 – and the heyday when people like Inez and Vinoodh were creating their first works with it – and I was blown away. That gave me the spark to want to work further with images, because these tools offered a possibility to explore the illusionary aspect of photography. My then boyfriend put me on the list to apply for the art academy. I was scared, it hadn’t yet occurred to me that I could be an artist, but I ended up at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, and later went to the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam.

-

-

GK: It’s amazing how often an artist’s childhood influences make sense. When I look at your projects, I see those influences: the natural history museum, the visual encyclopaedia. There’s this feeling of a wunderkammer, or a cabinet of curiosities. Were there any particular artworks you remember interacting with as a child?

KH: No, not really! I loved to dress up, to create my own worlds, stuff like that. It was at the art academy that I was really a kid in a candy store, because it was the first time I got some basic art historical knowledge. Maybe that shaped how I treat the visual elements of western art history now: as basic materials, stripped from their historical contexts. So no, not really any artworks! There was the natural history museums of course, but that’s very much in line with the wunderkammer idea. I was fascinated by the notion of the diorama: in a natural history museum, you very often have something like that which looks ‘real’ but in actual fact is not, and that’s of course a recurring theme in my work.

Another part of my childhood that proved quite pivotal was that I briefly had a little sister, who died as a baby when I was just five. After that, she remained a kind of imaginary presence who I kept talking to. In a certain way, her loss became part of a fantasy world that I liked to inhabit, to explore. I think my photography to begin with was often about escapism, trying to find relief or comfort or a feeling of homecoming, because I often felt quite alienated: first in my family, then in the academic world.

-

-

Wij, 2022

Bronze sculpture in public space in Leiden, The Netherlands -

Koen Hauser, Wij (US), 2022, Bronze sculpture in public space in Leiden, the Netherlands

GK: Nowadays, you’re obviously not someone who thinks in a very dogmatic way about photography – it’s something loose and malleable; you refer to ‘photographic works’ as opposed to photographs. This notion of fluidity extends across your use of different media, sometimes blended or mixed. Can you outline that?

KH: In the beginning – about 25 years ago – I didn’t really have strong ideas about what photography was or could be, nor why I liked it so much. But in actually working with the medium it really crystallized that it is the representational character of photography that I like. The illusion of photography. I’m interested in that mental aspect of what is perception and what is reality, so in that sense I don’t think photography is the only medium I want to use to express what I think. I used to say that I started taking photographs because I couldn’t draw!

In some of my projects, different media come together, but it’s also different dimensions in a certain way. Instead of talking about the strict historical division between certain media, I think about something that I want to express as data which can then unfold in two or three dimensions, or maybe more. Then it becomes a little more abstract! Photography is a way to make an imprint of reality using light, but a 3D scan that might form the basis of a cast for a sculpture is also an imprint of reality, comparable to the technique I used for the bronze sculpture Wij (2022) in Leiden. They’re quite similar. More and more, I think about photography as an imprint of reality, not as representing reality itself.

That being said, my projects aren’t strictly conceptual, even if they contain conceptual notions. As a kid, I used to make all kinds of weird-tasting potions and say it was magic, and my work now is similar: it’s something I cook up as a magician!

-

"Performéance! 18 years ago I was really happy with that – I invented a word!" - Koen Hauser

GK: You also refer to magic, performance – or performéance – ritual, illusion in your artist statement. It seems that you’re really striving for your work to deliver something fantastical, to trigger certain feelings and associations?KH: Performéance! 18 years ago I was really happy with that – I invented a word! Sometimes it confuses people: they think it must be a language mistake. But performéance for me is interesting because it refers both to a performance and to a kind of reenactment of a performance, so I like that meta opening it creates. It’s also about the illusion that you can actually understand what’s beneath the surface. In everything, there’s this need for me to understand what’s behind the reality I perceive, but at the same time there’s this conclusion – perhaps it’s human fate – that you can never really know. It then becomes about mystery. I think my work expresses itself as something that can evoke these feelings.Over the last few months I’ve been really into this book, The Case Against Reality by Donald Hoffman. He’s an American neuroscientist who theorizes that what we perceive as reality is actually just an interface, since we’re not capable of grasping the whole world. We only let through the information that helps us survive. It’s been really nice to look back at my work through this lens, because it’s in line with how I intuitively experience the world. Whilst I don’t have the answers to these big questions of quantum mechanics or metaphysical idealism, it’s more about the mystery of it all. -

-

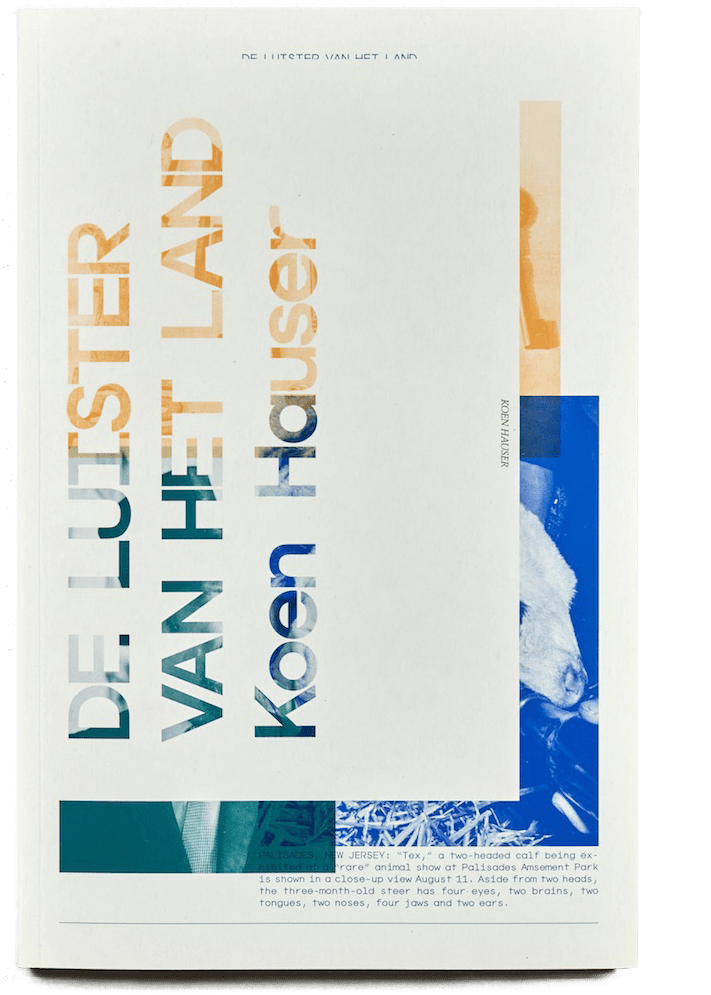

De Luister van het Land

2008 -

GK: Among your past projects, I wonder if there’s one that jumps out as really pivotal – where something really cemented in your practice?

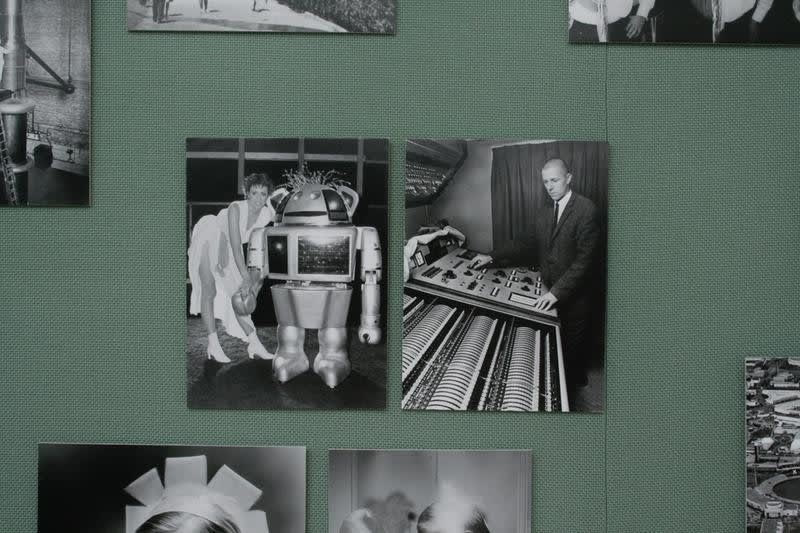

KH: I think the first very important moment was when I was invited to work with the Spaarnestad photo archive back in 2008. That led to a project called De Luister van het Land, which also became a book, where I really discovered my fascination for historical photography: material that’s grounded in some kind of collective memory. I was given carte blanche to make new work, exploring an archive of over 10 million images and selecting quirky things that stood out to me. Already in the first weeks, the notion of the diorama – of rebuilding reality – surfaced in a very illustrative way. It became a kind of encyclopaedia of an imagined world, made up of a field of associations that you could make your own stories with.

I was really able to time travel there and transcend my own personality; I ended up photoshopping myself into all these historic images, allowing me to be part of something that wasn’t in the here and now. I felt really deeply connected to it. I sometimes describe the project as a collection that features some kind of a Walt Disney figure in an imaginary world of his own design. I literally performed these characters, and every time you see me in a certain role, it’s about reality – about the difference between creator and creation.

Installation view of 'De Luister van het Land' at Galerie 37 Spaarnestad

-

-

Tableaux

28 February - 4 April, 2015 -

"I decided I simply wanted to make good photographs of stuff I like, and really just appreciate the physical appearance of these things, taken out of their original context." - Koen Hauser

GK: So there’s often this element of manipulation in your work, but it’s less pronounced in some of your other projects – Tableaux, for instance. I see you describe this project in quite ‘pure’ terms, though there’s still some manipulation going on in there?

KH: Tableaux came at a time when I was really done with everything around me, including the art world! I decided I simply wanted to make good photographs of stuff I like, and really just appreciate the physical appearance of these things, taken out of their original context. At that time, I had my studio in a building that also housed the depot of Rijksmuseum Boerhaave which is our national museum of science and medicine history, so that was really nice!

GK: A funny coincidence!

KH: Yes! And of course I loved that building. So that was how Tableaux came to life. I used the digital technique of photo stacking, which means the images are extremely large and hyperreal in quality, so you can really drown in them when you’re in front of them: you can even see the dust on the objects in the compositions. Seeing them on a computer screen doesn’t do them justice! In a sense, that project is also about reality and how far we can go into it, but on a more basic level.

-

-

Skulptura

18 May - 22 June, 2019 -

GK: And what was it like to work with digital image manipulation in the pre-AI days: what were the tools in your toolbox?

KH: Well I was always interested in different techniques because there’s always something at play which creates that magic of reality – a medium in between! I’ve done large format analogue photography, digital photography, photoshopping, I’ve made a stereo photography installation, a 3D movie. With my Skulptura series, I also started exploring 3D photogrammetry, modelling and rendering. AI is just the next chapter in following up these other techniques.

GK: But is AI making some of those earlier techniques redundant in the context of your practice?

KH: No, I don’t think AI makes other tools obsolete. What I like about AI is that I can easily make images that used to cost so much money, time and effort to create. At the same time, the process of making sometimes informs you on the work itself; doing stuff with AI can feel very empty because you put in a few prompts and you’re given thousands of options. Back in 2001, I made a little booklet about my sister who passed away, trying to picture what she would have looked like at 24. It took me about six weeks to create anything close to a portrait – but nowadays we’d just input an image of her mother, her father, her siblings, and there would be countless options! But of course, it wouldn’t have provided me with much meaning. In that sense, I think it’s nice to use these tools and techniques alongside one another. AI also tends to render towards the most common or conventional way of representing something, so the creativity lies in how you use it.

-

"When people look at the work, they tend to wonder how it came to life, and I think that’s important." - Koen Hauser

GK: Your Skulptura project is probably the work I know best: could you describe that for us?

KH: Skulptura is a kind of reflection on my different ways of trying to grasp the nature of sculpture – a medium of time and space – juxtaposed to photography. On the one hand, it’s about photography as this representational medium that gives you an illusion of something you can’t really touch, so there’s this disconnect between the image and reality. The collection of images that make up Skulptura, as well as my source material – which I always think is important to showcase alongside it – is the result of all kinds of techniques, of building and merging. In the end you can read it as something very fluid: there’s no clear distinction between two dimensions and three dimensions in what you see. When people look at the work, they tend to wonder how it came to life, and I think that’s important. If I were only to explain my technique, what I was doing, that sense of mystery and magic is gone. That’s maybe the essence of what I want to convey, hiding the structure and showing only the output. That’s maybe an analogy with alchemy, where you present an enigma to be approached in a more abstract way.

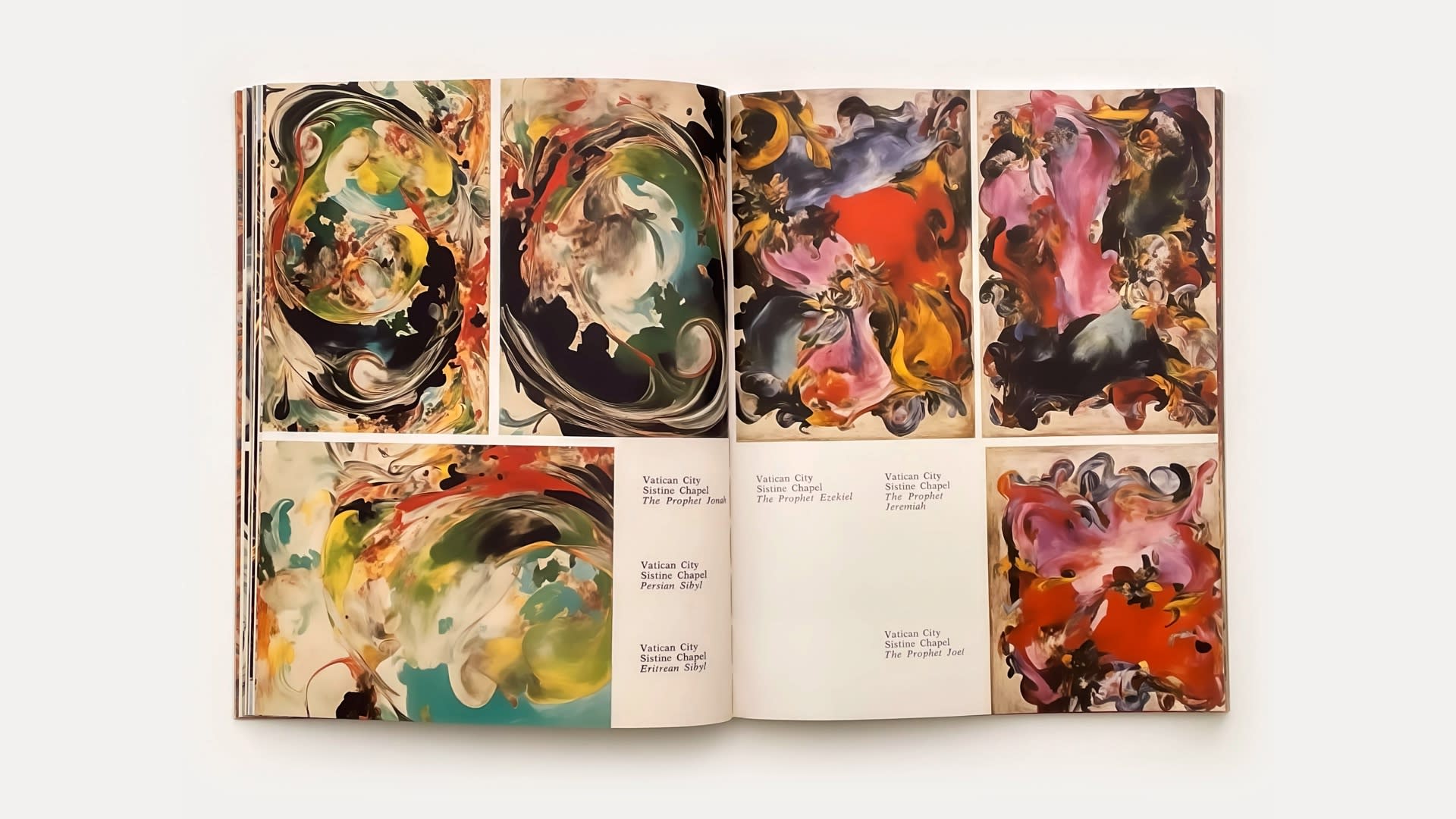

GK: And the source images you’re reworking are primarily archival images?

KH: Yeah, mainly printed images from old books. That’s an important aspect, because it makes my works a kind of distorted reproduction of a reproduction. I also used archival images from the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum: that’s those two big large of a space with sculptures installed there. Although it’s definitely a kind of meta loop – the idea of a representation of a representation of a representation – it’s not that I want people to talk about that aspect in a really cognitive way. It’s more interesting that you feel that in your body or try to grasp at it visually!

GK: When I look at the distorted sculptures in your images, I find them quite aesthetically appealing, but I’ve seen you call them unsettling in the past. Why do you think that is?

KH: Well, the unsettling part is your awareness that it’s a representation: you know that you can’t actually touch it, it’s locked somehow in two dimensions. It’s about not being able to fully reach them: we might long for something that’s transcendent but all we have in the end is this interface through which to interpret the world around us. But it’s not only a limiting factor – it’s also about celebrating our sensory engagement with the world, because it’s the only way we can know it!

-

Michaelangelo Iconoclastia

2024 -

Koen Hauser, A variation of the Cover of a Michaelangelo Iconoclastia magazineGK: This leads us of course to your latest work, Michelangelo Iconoclastia, which is still coming to life. Could you try to introduce it?KH: So I often work with printed images, but the particular book I’m reinterpreting in this project is essentially ‘art for the millions’, because it’s a tourist book on Michelangelo sold in huge volumes to visitors in places like Rome or Florence. I found my copy in a second hand bookshop, but I actually see it a lot: it’s very common! That’s one of the reasons I like it, that it reflects a very stereotypical, clichéd version of what art history is.By making numerous variations of this book, I’m expressing the endless appearances that an original image can take on, pointing to a shared origin, perhaps. I’ve already had over 30,000 images generated, because there’s no limit to the number of images you can make with AI! Of course, I’m not only interested in making interesting images, but more so in presenting them in a way that says something about technique. Each variation reflects changing forms, appearances – I think about them as new ‘apparitions’, which also has a slightly spiritual connotation.So, I plan to make a total of 104 reworked versions of this book, presented as an installation where viewers can flip through each one, until they’re totally baffled by the infinite possibilities. That’s the core of it: of sharing that ‘wow’ experience I have when working on it. It’s analogous to my take on reality – that it’s something that can be unfolded in so many different ways. Each version explores a specific visual motif or theme that originates from my archive of cut out imagery. I’m still producing a lot, and with every volume I conclude, the better it expresses the core of what I want to present.

Koen Hauser, A variation of the Cover of a Michaelangelo Iconoclastia magazineGK: This leads us of course to your latest work, Michelangelo Iconoclastia, which is still coming to life. Could you try to introduce it?KH: So I often work with printed images, but the particular book I’m reinterpreting in this project is essentially ‘art for the millions’, because it’s a tourist book on Michelangelo sold in huge volumes to visitors in places like Rome or Florence. I found my copy in a second hand bookshop, but I actually see it a lot: it’s very common! That’s one of the reasons I like it, that it reflects a very stereotypical, clichéd version of what art history is.By making numerous variations of this book, I’m expressing the endless appearances that an original image can take on, pointing to a shared origin, perhaps. I’ve already had over 30,000 images generated, because there’s no limit to the number of images you can make with AI! Of course, I’m not only interested in making interesting images, but more so in presenting them in a way that says something about technique. Each variation reflects changing forms, appearances – I think about them as new ‘apparitions’, which also has a slightly spiritual connotation.So, I plan to make a total of 104 reworked versions of this book, presented as an installation where viewers can flip through each one, until they’re totally baffled by the infinite possibilities. That’s the core of it: of sharing that ‘wow’ experience I have when working on it. It’s analogous to my take on reality – that it’s something that can be unfolded in so many different ways. Each version explores a specific visual motif or theme that originates from my archive of cut out imagery. I’m still producing a lot, and with every volume I conclude, the better it expresses the core of what I want to present. -

"But I’m much more concerned with how money is being made and distributed through these systems – solely aimed at financial profit– than I am from a creative perspective." - Koen Hauser

GK: What have you learned about AI in the process of making this project?KH: I read a lot about it, but I think the learning aspect is more about actually using it. It gave me a profound and visceral understanding of how expressive forces compete, conjure, combine and in the end create something visual. I think this experiential aspect is pivotal in the light of the current discourse in contemporary art that has become so highly theoretisized and intellectualized. I don’t want this work to illustrate my intellectual findings on AI, I want people to engage with the vast amount of interrelated images and personally experience how expressive forces compete, conjure and combine in creating our visual perception of the world around us.I also really like that the output is sourced in some way from a collective consciousness, which makes me think of research by the likes of Campbell or Jung. I know a bit about how AI works, how there’s this fear that it can make people believe things that aren’t there. But that’s what I’ve been interested in for the last decade already! That we shouldn’t believe things are real just because they look photographic. Obviously AI is evolving, but for now it really outputs quite boring averages of how things look – a common denominator that feeds off stereotypes, biases. It isn’t massively creative!GK: I guess many artists are concerned with AI in terms of copyright infringement – that their works become source material for new images without their consent.KH: I completely understand, and I know that my work is also in these AI training sets: there’s a website where you can check quite easily. I personally don’t mind, because I like the idea that my images become food for new life to evolve from, but I recognize that’s a very philosophical take! On a day to day basis, it’s a struggle to sustain an artistic practice both in financial terms and in the acknowledgement of our personal endeavours. But I’m much more concerned with how money is being made and distributed through these systems – solely aimed at financial profit– than I am from a creative perspective. -

-

To discover Koen Hauser's work up close, be sure to visit one of the following exhibitions:

Current exhibitions:

'Paleis van Fotografische Sculpturen' (Palace of Photographic Sculptures) at Museum Hilversum, featuring work from Koen Hauser's most recent project Michaelangelo Iconoclastia (2024) and Skulptura (2019). The exhibition is on show untill 22 September, 2024.

Artist Talk:

Museum Hilversum and Koen Hauser have the pleasure to invite you for an artist talk on Tuesday September 17, 2024 from 7:30 PM onwards. If you would like to attend please email us at info@theravestijngallery.com.

Upcoming exhibitions/art fairs:

Group presentation at the inaugural edition of NAP+ featuring new works by Koen Hauser, Thomas Kuijpers, and Ruth van Beek.

Festive opening: Thursday 12 September from 19:00 - 21:00

Fair days:

Friday 13 September from 11:00 - 19:00

Saturday 14 September from 11:00 - 19:00

Sunday 15 September from 11:00 - 17:00

'MAN: Portretten uit de Collectie' (MEN: Portraits from the Collection) at Fotomuseum Den Haag, presenting works from its collection by male photographers who consciously or unconsciously engage with masculinity, revealing its complexity. Featuring pieces by Koen Hauser, Hans Eijkelboom, Samuel Fosso, Erwin Olaf, Paul Blanca, Yasumasa Morimura, and Thorsten Brinkmann, the exhibition explores how these artists understand and express their gender, offering a multifaceted view of masculinity.

On show from 17 August to 1 December, 2024.

To discover more, visit our website at www.theravestijngallery.com. Feel free to reach out to us at info@theravestijngallery.com if you would like to receive more information or acquire one of Koen Hauser's pieces.

-

Exhibitions

-

Museum Hilversum | 'Palace of Photographic Sculptures'

Koen Hauser 6 June - 15 September 2024'Paleis van Fotografische Sculpturen' features works from his 'Skulptura ' series and new photographs from the 'Michelangelo Iconoclastia' project. For 'Michelangelo Iconoclastia ', Hauser visually reinterpreted an old tourist guide... -

'Skulptura'

Koen Hauser 18 May - 22 June 2019In the words of author Merel Bem, “Koen Hauser never starts from the idea that a photo should represent reality in a direct way. As a photographer with a deeply... -

'Tableaux'

Koen Hauser 28 February - 4 April 2015Koen Hauser got his first degree in Social Psychology before he graduated in Photography at the Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam. This combined background of social studies and art serves as...

-

-

-

Publications

-

-

Press

-

Het gesprek - Koen Hauser

September 22, 2022Annemieke Bosman in gesprek met fotograaf Koen Hauser. Hauser, nog niet zo lang geleden Fotograaf des Vaderlands, doet mee aan BredaPhoto Festival. Het tiende BredaPhoto Festival dat tot en met... -

Expositie Review

May 16, 2019 -

Sight Unseen: Koen Hauser

October 10, 2019This Dutch Artist’s Warped Archival Photos Are the Break From Reality We Need Right Now in The Ravestijn Gallery in Amsterdam With the state of the world the way it... -

De Kunst van het Scannen

November 18, 2017Fotograaf Koen Hauser maakte het campagnebeeld voor PAN 2017. Hij koos voor 3D-techniek. 'Die leek me goed toepasbaar.' 'Het was best gek, want ik ben natuurlijk fotograaf, maar voor dit... -

All Is Lost

July 7, 2016 -

De Jonge Jaren van Koen Hauser

August 12, 2014[English text below] Koen Hauser (1972) is, in navolging van Ily Niokiktjien, onlangs benoemd als Fotograaf des Vaderlands. Momenteel werkt hij vanuit die titel aan een project dat hij in... -

The Artist as a Creator

October 17, 2009Anyone who thinks that Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) is famous purely for inventing the daguerreotype – and along with it, photography – is doing him an injustice. Daguerre achieved great renown...

-

-

-

OTHER EPISODES

-

In Conversation With: Anja Niemi

b. 1976, Norway -

In Conversation With: Mathieu Asselin

b. 1973, France -

In Conversation With: Jean-Vincent Simonet

b. 1991, France -

In Conversation With: Nico Krijno

b. 1981, South Africa -

In Conversation With: Eva Stenram

b. 1976, Sweden -

In Conversation With: Katie Burnett

b. 1985, USAA stylist by trade, Katie Burnett has always collaborated closely with photographers across assignments in fashion. But periods of pandemic lockdown, when she was unable to work on set, were... -

In Conversation With: Pacifico Silano

b. 1986, USAWorking as a lens-based artist, Pacifico Silano strives to appreciate gay identity through (gay pornographic) magazines from the 1960s, 70s and 80s. He interrogates the line between desire and masochism,... -

In Conversation With: Theis Wendt

b. 1981, DenmarkOften illusionary, occasionally subversive, and invariably crafted from a broad toolbox of materials and techniques, Theis Wendt’s works reflect his preoccupation with age-old questions of the human relationship to authenticity.... -

In Conversation With: Michel Lamoller

b. 1984, GermanyLast two weeks to see the acclaimed exhibition Anthropogenic Mass by Michel Lamoller, on show till Saturday June 18. An exhibition illustrating the mass of everything manmade which is now... -

In Conversation With: Mark Mahaney

b. 1979, USAAs a gallery we are always on the lookout for work that fascinates, resonates if you will, and sticks to you. Work we would like to acquire for our own...

-